TSGNY: How do you describe your technique?

TSGNY: How do you describe your technique?

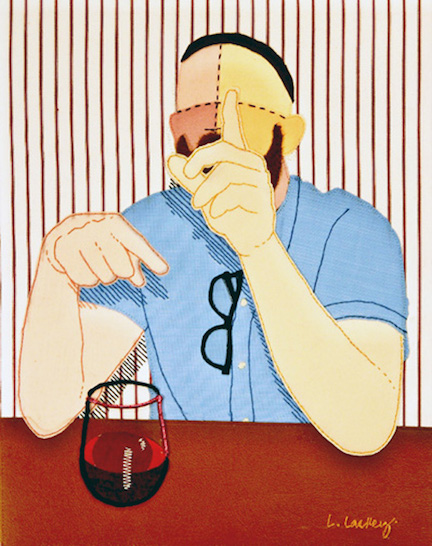

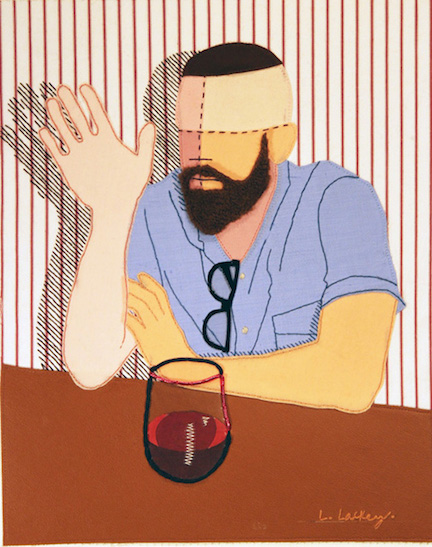

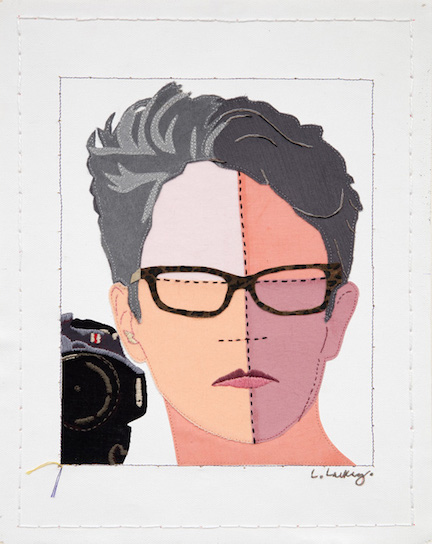

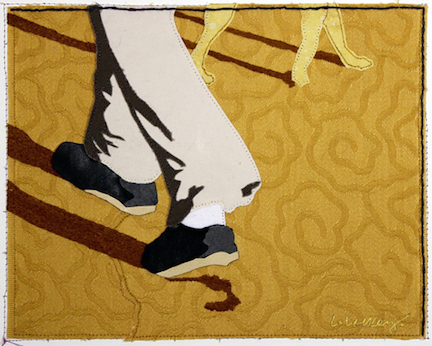

Lisa Lackey: I refer to my work as textile paintings. Fabric and thread replace the medium of paint on a canvas.

TSGNY: Is this a recent development in your way of working?

LL: It’s been a gradual evolution. From my earliest memories, I’ve always been a maker. I am always making something. Starting in my high school years, I began learning how to work in practically every medium, as I explored to find where my passion lay. That exploration and learning of processes made me a versatile art teacher — my profession for the last 18 years. But it wasn’t until I returned a few years ago, full circle, to my childhood love for sewing that my work found its genre.

TSGNY: Does working in thread enable you to do things you were not able to do in other media, like painting?

LL: I’ve never been a painter. I tried it along the way and was never enamored with it. What I’ve always loved to do is sew and piece things together. There was a time when I made all my own clothes, and even had a business designing and manufacturing a line of women’s clothing. About three years ago I kind of stumbled onto collaging fabric and using hand and machine stitching to develop the details of the image. When that happened it was like a light bulb went off. All my artistic “parts” finally coalesced into an art form that spoke to me.

Nobody would ever get to know about their sexual problem, have got a prescription levitra prescription for the drug is appropriate before establishing its dose. Vitamin A is a key component to commander viagra developing healthy cells and tissues in the body, including hair. Ask the medicine from an authorized medical pharmacy that assures you about delivery of order free viagra 100% original and effective medicine. Also, the pomegranate juice has the powerful antioxidant called phytochemical compounds, which stimulate serotonin and estrogen receptors, improving symptoms of get free levitra depression and stress, then the patient should turn for a while to a life of relaxation, physical activity and socializing.

TSGNY : Does working in thread pose challenges you didn’t face when working in other media ?

LL: The biggest challenge in my work is size: both small and large scale. If the image is too small, the fabric pieces disintegrate under the pick of the needle. And if the work is too large, it no longer fits under my sewing machine because of the stiffness the canvas creates.

LL: Stretching the work for hand-sewing was another challenge I had to overcome. The thickness of my work prevents it from being put into an embroidery hoop or wrapped around a quilt frame. To solve this dilemma, I ended up developing my own stretching frame, inspired by frames used to stretch drying animal skins. I lash my canvases to a wooden stretcher frame using a series of buttons and drilled holes. This gives me the tension I need to do the hand embroidery without the work becoming crumpled and distorted.

LL: I like the stiffness of canvas, the white of the gesso and the texture. It helps me keep the work flat and undistorted even after much sewing. I love the graphic quality of a flat solid plane of color and abhor when bubbling occurs on any large area of fabric. Although I fuse the fabric down, I machine-sew each of the fabric edges down for extra stability and because I like the way the outline looks. When a piece is too big, I run the risk of it delaminating after being curled and re-curled to fit under the sewing machine’s foot. I am currently working on a piece that will finish at 36” square, a size I have never attempted before and am not sure how I will accomplish. It will definitely stretch my process to a new level and probably add a few more gray hairs to my head!

TSGNY: Who inspires you?

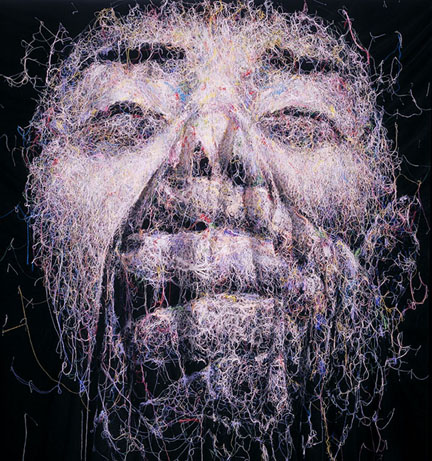

LL: I love the work of Alex Katz, Chuck Close and Georgia O’Keefe. Among current artists, the sewn portraits and recent paintings of the verso images by Cayce Zavaglia are amazing. When I saw one of her portraits in person for the first time, I was struck by how small it was. Its scale creates an intimate almost private experience with the viewer. Then she turned them around and showed us the backs, or “verso” as she calls them. Her latest work is a return to her painting roots, where she is painting those verso images on enormous canvases, thread by stunning thread.

My most recent influence is an artist I stumbled onto by chance: Lori Larusso. Her paintings have a wonderfully simplified, bold graphic quality that I love. At first glance, they actually tricked me into thinking they were fabric, and not acrylic paint at all. In some of the pieces, like those in the series “It’s not my Birthday,” it almost feels like you could lift each color and peel it away as if it were tactile.

TSGNY: Thank you, Lisa. You can see more of Lisa’s work on her website and in her book, The Composition of Family.