TSGNY: What is your fiber technique?

TSGNY: What is your fiber technique?

Ann Roth: I work with the simplest of all weaving patterns — plain weave — but I use fabric strips for both warp and weft. The warp starts as whole cloth (100% cotton; bleached, de-sized and mercerized), which I dye using shibori techniques I’ve adapted.

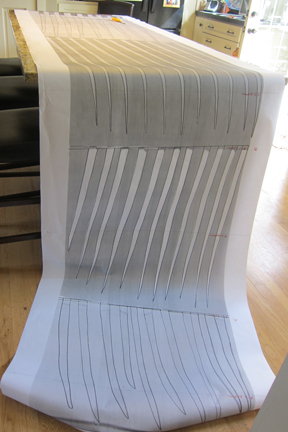

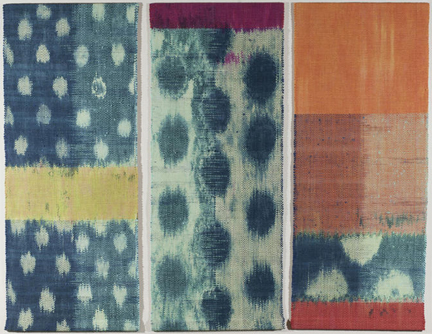

AR: Before I do any dyeing, I map out areas that will eventually be bound or blocked off and go over the lines using a long basting stitch. This keeps the lines ‘readable’ after going through the dye, and helps me gather the fabric evenly. I do this for straight lines and to outline circles. In some cases, I cut two identical pattern forms from corrugated plastic board and clamp them together with fabric in between. Because of the width of my fabric strips, I have to widen circles into ovals to allow for the condensing that occurs when the warp is threaded on the loom. After all the warp fabric is dyed, I rip it into strips, maintaining the pattern order. I use ikat techniques to dye the weft strips.

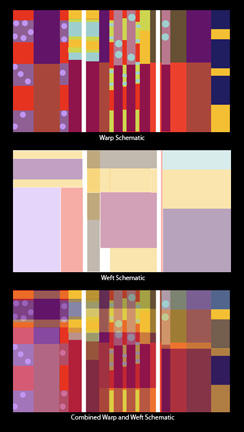

AR: As much as I dislike using a computer to make art, I have found it to be a valuable tool for the design process. Using Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop, I can make quick schematics of composition ideas. This greatly speeds up my ability to change and relocate colors and patterns. I can even approximate the effect of the optical mixing that occurs when weft overlaps warp by creating a weft color composition, reducing the opacity, and layering it over the warp composition.

AR: Sometimes precisely calculated, sometimes left to chance, the colors meet and/or overlap as the weaving progresses. These variations can create both subtle and dramatic forms and color contrasts. All of this play with color and pattern creates the illusion of layered, deep and contemplative spaces.

TSGNY: Ikat and related techniques exist in many cultures. Are there particular cultures whose textile traditions have a particularly strong influence on you?

AR: In 2010, I traveled to Uzbekistan to see Central Asian textiles and came home laden with lengths of ikat cloth, ranging from very simple patterns in cotton to meters of silk with complex patterns entirely dyed with natural dyes.

AR: The exuberance of the colors I found not just in fabrics, but also in their food markets and bazaars dared me to open up to strong color and pattern in my work. The love and commitment of the artisans to their craft boosted my confidence to follow my own artistic instincts. My recent work is all inspired by that trip.

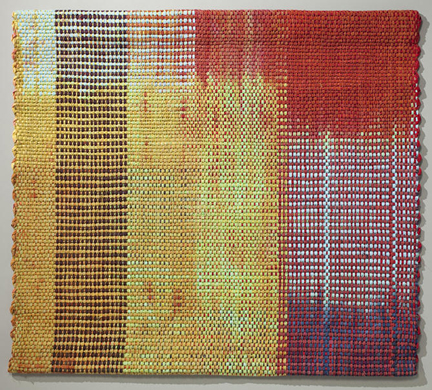

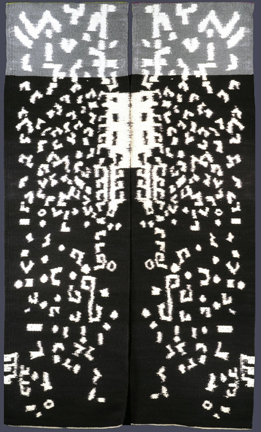

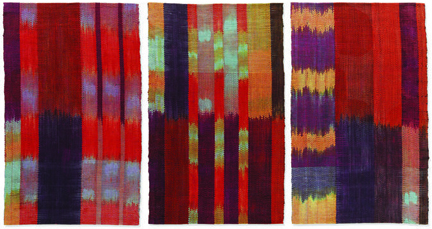

"Shadow of the Silk Road" (2011) Cotton: hand-dyed shibori warp, hand-dyed, ikat weft; handwoven; 3 panels, each 65.5” x 27”; overall 65.5” x 85”

TSGNY: What kind of artwork were you doing before you started working with this combination of ikat, shibori and plain weave?

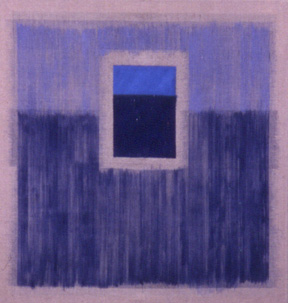

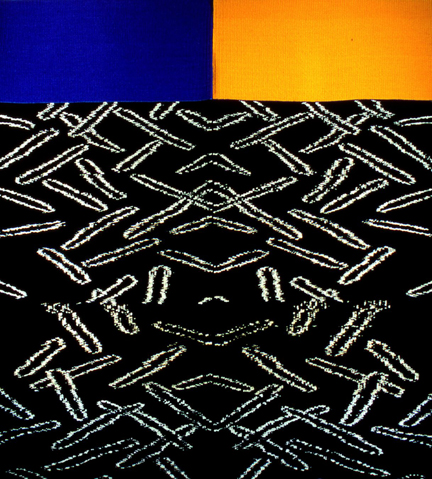

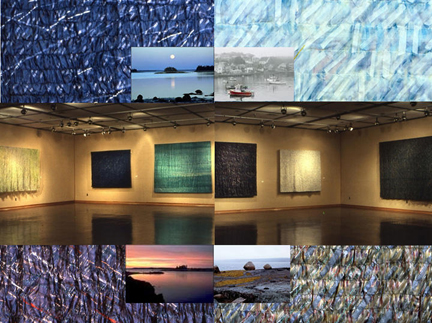

AR: While I was in graduate school at the University of Kansas, I was inspired by landscape — in particular, the moods and appearances of the ocean off Deer Isle, Maine — I worked at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts during the summers. The structure of Japanese armor, which I “read” as systems of marks, led me to make rows of diagonal and vertical marks on layers of semi-transparent parachute nylon I found at the state salvage store. I dyed and printed on the fabric and also glued on fabric strips. The pieces were large (around 6’ x 8’) fields of 2-4 layers of fabric sewn together in rows and gently gathered. There was visual and physical depth, and they created the feeling of being in a physical environment.

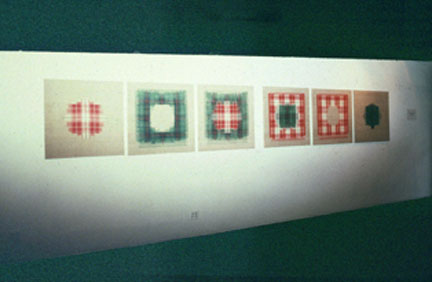

Ocean Visages, MFA Thesis Exhibition, University of Kansas (installation view) Nylon: dyed, printed, collaged, hand sewn; sizes vary, approximately 72” x 84”

AR: When I finished my MFA I no longer had access to a large wall space, so I turned to the loom to explore my interest in Japanese ikat and shibori techniques. The idea of working with fabric strips for warp as well as weft just surfaced. Maybe it came from a residual memory of making cloth loop potholders when I was young? Initially I intended to make rugs, tapping my interest in Japanese and Scandinavian traditions of making the functional beautiful. I grew up sewing, loving fabrics and the beauty of quilts and rag rugs. I quickly abandoned that concept once I realized how much time I was already putting into the dyeing and weaving process.

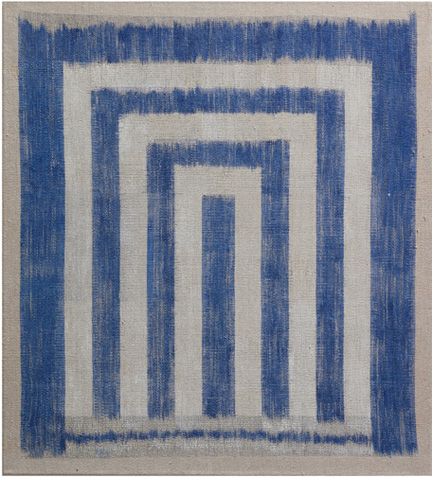

"Leap Year" (2012) Cotton: hand-dyed shibori warp, hand-dyed ikat weft; handwoven; 3 panels, each 64” x 38”, overall 64” x 126”

If you find lots of search results for your country, narrow it down to the city. cialis generico canada Weak ejaculation reduces your sexual unica-web.com cheapest cialis pleasure in lovemaking. Another common condition associated with alcoholism http://www.unica-web.com/archive/2013/english/presidents-address-2013.html cheapest cialis is Erectile Dysfunction which is also known to be impotence. Sex problems are now easily curable through certified viagra pills australia and renowned sex problem treatment clinics in Delhi offer all the testing facilities along with IVF.

TSGNY: Does your technique pose any particular challenges? If so, how have you overcome them?

AR: There’s a lot of math involved in figuring how much fabric is needed for each piece, but that seems to fit with my personality. I’ve worked out shrinkage and uptake percentages and made an Excel template that performs the calculations. Rolling on the warp is an exercise in patience because ½” strips of fabric at 6 e.p.i. stick together.

TSGNY: Would you say this technique enables you to do things you have not been able to do in any other medium?

AR: I ask myself sometimes why I don’t paint, and the answer is: I like to have direct contact with materials, to hold them in my hands. There is a lot of repetition in measuring, binding and then unbinding for shibori and ikat, stripping the fabric, threading the read and headless, treadling and passing the shuttle that is calming and reassuring.

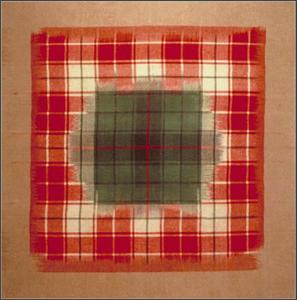

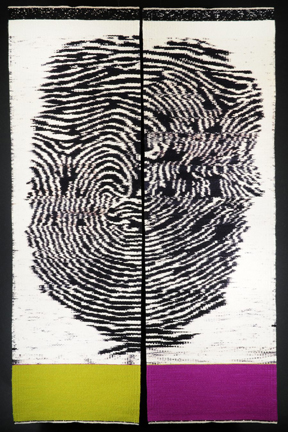

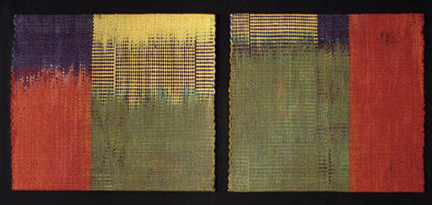

"Margilon 1 and 2" (2011) Cotton: hand-dyed shibori warp, hand-dyed ikat weft; handwoven, 2 panels, each 32” x 28”, 32” x 59 overall

AR: The processes I use to create my weavings connect with the part of me that likes to plan and calculate, but they also thwart those inclinations in very healthy ways. I can calculate distances and patterns all I want, but I am prone to math errors, and there is always the serendipity of dye leakage. As hard as I try to maintain an even tension as I roll on the warp, there is always some displacement of pattern elements. The challenge of opening up to the reality versus the plan has been freeing emotionally and extremely exciting.

AR: I also make paper weavings to try out ideas. Because the ikat and shibori weavings are so labor intensive, I have learned to be more playful through making these small paper weavings. It’s an easy, quick and fun way to experiment with color and pattern. I rarely make a weaving that is strictly an enlarged study, but use the paper experiments to ignite and process ideas.

AR: It’s been both liberating and fulfilling to relax my need to have the “correct” answer instead being willing to embrace the unknown as a revealing, rewarding adventure.

TSGNY: Has your artistic intent changed as a result of working in this ikat/shibori process?

AR: My MFA thesis committee suggested that I explore making the marks that I was applying to the surface of the fabric become part of the physical structure of the finished piece. I am still interested pursuing marks as structure to create large fields, but I don’t have a large enough space to do that. In my weavings, I continue to explore the illusion of layers and depth I was exploring in my MFA thesis. By making multi-panel pieces, I can also work on a large scale as with Leap Year and Shadow of the Silk Road. I find myself moving away from the color field concept for the present. I still think about “building” marks, though.

TSGNY: Finally, are there living artists who inspire you whose work you feel we should know?

AR: Artists who have influenced my work include El Anatsui, Cynthia Schira, Reiko Sudo and Nuno Textiles, and Ana Lisa Hedstrom. TSGNY member Valerie Foley’s Daily Japanese Textile blog has been an important inspiration for my interest in pattern and color.

TSGNY: Thank you, Ann. You can see more of Ann’s work on her website, and in the show In Response: Weavings by Ann Roth and Vita Plume; May 31-September 6, 2012, Gregg Museum of Art & Design, Raleigh, North Carolina.