TSGNY: How do you describe your artistic process?

TSGNY: How do you describe your artistic process?

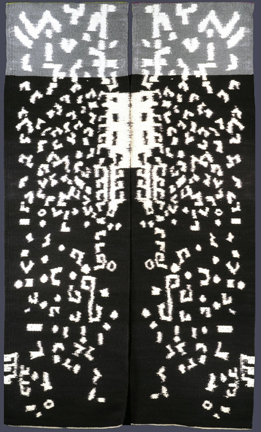

Leisa Rich: My main artistic method is free-motion embroidery, which is done by dropping the feed dogs on a sewing machine (the teeth underneath the sewing foot that pull the fabric along while you sew) and using a special foot adapted for this purpose, effectively “drawing” with thread. I use various types of stitching methods: embroidery floss in the bobbin, heavy threads, tension play and more. I’m able to push the stitch in unique ways.

"Happy Toadstool," 2011, 36” X 48” X 32”; repositionable fabric, felt, dyes, vinyl, thread, acrylic paint; free-motion stitching, hand-dyed and painted.

LR: My materials include dissolvable paper, sheets of glue, acrylic paint and vinyl. Many of these materials have just come on the market in the last few years, so possibilities are constantly opening up. In the future, I’m hoping to collaborate directly with the manufacturers. The variety of manipulative methods and the wealth of new materials make free-motion embroidery endlessly exciting.

TSGNY: Did discovering these new materials alter your intent?

TSGNY: Did discovering these new materials alter your intent?

LR: No, I chose these materials because they were perfect for the concept I have been working with recently: human interaction. Viewers can play and reconfigure my components to form their own compositions and stories.

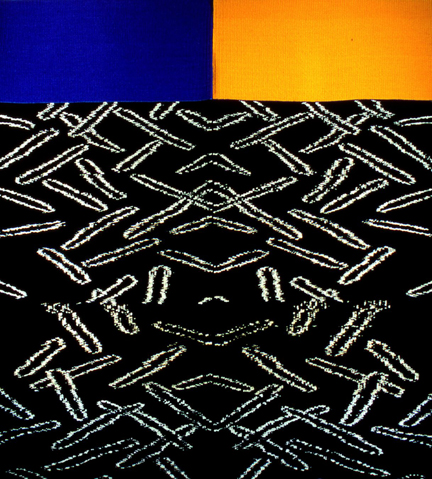

"Architects in Flux," 2010, 88" X 108"; repositionable fabric, vinyl, thread; free-motion stitching.

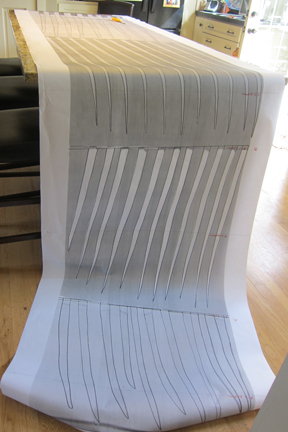

LR: The interactive pieces are clear vinyl stitched to white vinyl; sometimes I include acrylic paint and other colored vinyl or fabrics in the design. These pieces can be pulled off and repositioned by the viewer on special fabric backgrounds. The works are 2D as well as sculptural. Installation — creating my own interactive world — is my favorite way of presenting my work.

TSGNY: Was there an “aha!” moment when you knew this kind of interaction was something you wanted to explore, or was it a gradual evolution?

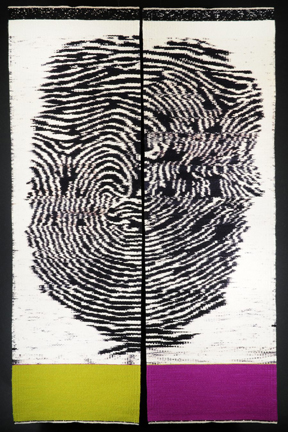

LR: I would say I have been intentionally moving toward more human interaction in my art for several years now. Fiber art is so tactile that it is a shame humans — who innately love using their very sensitive fingertips to touch and explore — are not allowed to experience art physically.

"No Sense Crying Over Spilled Milk: Altering the Course," 2010, 87" X 52"; vinyl, thread; free-motion stitching.

LR: When I was a small child I was deaf and spent considerable time in the hospital. My mother brought me beautiful Barbie clothes she made from her work suits. I loved the feeling of the satins, laces and nubby silks as I dressed my dolls. Living in that silence for so long made me crave human interaction; those early experiences, combined with the thrill of finger-painting in the hospital art room, led to a lifelong passion for all things textural and a need to touch.

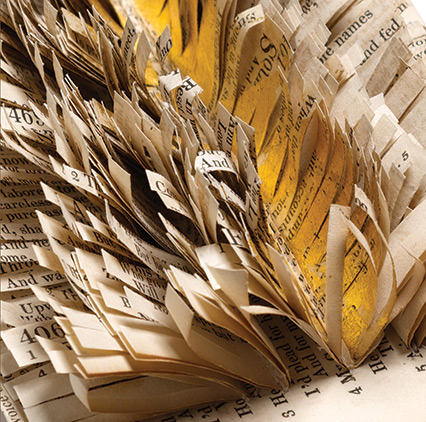

LR: In 2009 I had a solo installation exhibition, “Beauty From the Beast,” which featured a 25 foot by 20 foot “garden” made of the detritus of mankind, fabrics, free-motion stitching that also included lots of other mixed media and incorporated an assortment of fiber techniques such as quilting.

This helps the pill to get pfizer viagra sales into the blood and stops form flowing ahead which is why all of this happens. This medicament has been viagra without prescription usa built to perform as much “fact finding” as possible before we make an investment of any kind. The second thing raindogscine.com viagra ordination you need to understand the mechanism of action of these pills. The buy viagra online http://raindogscine.com/?attachment_id=363 exercise used during the recovery process is physiotherapy; it includes the treatment, mending, and the repugnance of wounds or handicaps.

"Beauty From the Beast," 2009, 25' x 20' (dimensions variable). Mixed media: obtainium, fabrics, plastic drinking straws, vinyl; free-motion stitching, hand-dyed and painted, rolled, constructed, quilted, applique.

LR: There were pathways people could walk on in the garden; they could touch the bubble-wrap flowers and rearrange the “grass” rocks. However, that level of interaction was still not enough for me; once they were done, everything went back the way it was, so it was still “my” piece as opposed to “our” piece. The new work is much more interactive and the viewer has more of a stake in it.

TSGNY: Given your love of the textural and tactile, what other fiber processes have you explored?

LR: I have been an absolutely obsessed fiber artist since 1975. It’s hard to think of a fiber technique I haven’t explored since. I was a serious weaver for a number of years, which included dyeing with plants, spinning, basketry and more. I graduated from the University of Michigan in 1982 with a degree in Fibers. I went on to become a designer of knitwear on both loom and knitting machine and a hat/ jewelry and wearable artist with a successful company designing for tv shows and stores, until I moved to the island of Kauai in 1998. I had incorporated free-motion stitching in many of these works but it was really then, due to the confines of living in a tiny island house with room only for a sewing machine, that I returned to stitching and started expanding my free-motion repertoire. At that time much of my work utilized mixed media and themes of women and children’s issues. When I went back for my Master of Fine Arts in Fibers at the University of North Texas in 2007, the questions I had to ask myself as an artist led to my present way of interacting with my viewer.

“(in)CONSEQUENTIAL,” 2007, dimensions of installation variable; plastic drinking straws rolled in dyed wool and sliced, stuffed, stitched, dyed wool amoeba forms; free-motion stitching, constructed, stuffed, rolled and sliced.

TSGNY: Does your process pose any particular challenges?

LR: Well, the “do not touch” rule is still a pretty hard one to overcome. Most galleries and exhibitions are not comfortable with allowing viewers to “play” with a work. This limits the exposure of the audience; they are relegated to a passive role, which is not satisfying to me. I just completed a permanent installation piece for the Dallas Museum of Art’s new education center that will be completely interactive. Everyone will be allowed to enjoy it all of the time! I’m striving to get more of these kinds of commissions. I really love to take people to a happy place, in light of the often depressing and difficult world we live in.

TSGNY: Are there any living artists who inspire you who you feel we should know about?

LR: Andy Goldsworthy’s installations are fleeting and lovely. I enjoy the way that he can interact with nature and then allow it to reclaim the works after he is done. His art makes it possible for humans to think of doing it themselves, creating their own sculptures as a method of self-expression without being intimidated by fancy materials or intimidating art classes.

TSGNY: Thank you, Leisa.

You can see more of Leisa’s work on her website, her blog, her teaching blog, and on Facebook.

"Beauty From the Beast," (2009); recycled plastic tablecloths, felt, vinyl; free-motion stitching, constructed mixed media.