Larry Schulte: I have never worked in just one medium. The two kinds of work that I’ve done most extensively and have exhibited the most are woven painted-paper pieces based on the Fibonacci sequence, which I have been making for nearly 40 years; and screenprints, which I have been making for about 10 years.

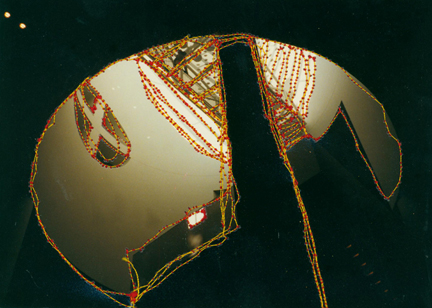

LS: I also make small works that I can create at home rather than in the studio. These include woven photographs, paper-punched photographs, and stitched prints and photographs. I like to play with a variety of media – each medium teaches me something that I can apply to the other work.

TSGNY: How does working in a smaller format in other media inform your larger work?

LS: The small woven-photo pieces don’t take much time — I can complete one in two to three hours. The photos are of patterns and textures that I might want to create in a larger work. With the small woven-photo pieces, the image is already there, so I don’t have to spend additional time in image preparation. This lets me see in a single evening how a circle image will interact with a square pattern image, which I can then translate into a larger woven painted-paper piece, or a screenprint. Similarly, the paper-punch pieces let me see immediately the results of layering one pattern over another pattern.

TSGNY: How did you begin the woven-paper work?

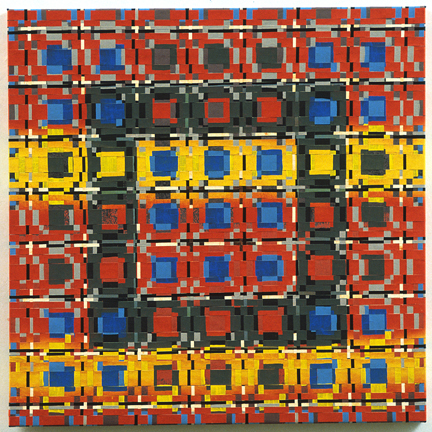

LS: I was getting my Master’s degree in watercolor and at the same time I was taking several weaving classes. At some point, I started weaving a paper weft into the fiber warp on a loom. Eventually I did away with the loom altogether and wove paper with paper by hand. I start with two pieces of heavy white all-cotton paper, paint each piece with acrylic paint (one for the warp, the other for the weft), cut them into strips and weave them together.

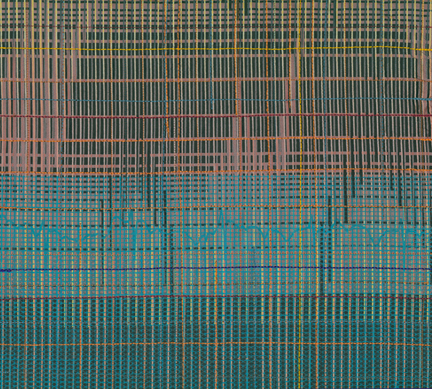

LS: When I was weaving on a loom, I worked with all kinds of techniques: ikat, overshot patterns. The woven painted paper pieces have a more simplified structure. Originally, I used a plain weave, simply over-under. As the works increased in size, I made a modification to a twill weave, over two under one. This modified twill was also an iteration of the Fibonacci Sequence. The twill weave also allowed the strips of paper to be closer together in a tighter weave, which keeps the painted image more intact.

LS: The work has never really been about the medium, though, it was about creating a visual image of mathematical structure. It’s just that the woven painted-paper medium was one of the most satisfactory ways I found of creating a visual structure.

TSGNY: That visual structure has a strong mathematical basis. How did the Fibonacci sequence come to play such a central role in your work?

LS: I chose the Fibonacci sequence many years ago, for several reasons. I was a mathematician before I ever started making art. I have a degree in mathematics, and taught math for a few years. Yet when I first started making art, I was painting landscape. I grew up on a farm, and nature is an important part of my work. In a way, I feel that all of my work is landscape. The Fibonacci numbers are related to the structure of nature. They occur in everything that is a spiral: pine cones, seashells. One of my favorite places the numbers show up is in the head of a sunflower. There are two spirals of seeds in a sunflower head, one clockwise and the other counter-clockwise. The numbers of seeds in the two spirals are always two consecutive Fibonacci numbers. The width of the strips I cut always varies proportionally to the numbers in the Fibonacci Sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, . . . each number always the sum of the two previous numbers).

TSGNY: Your other main body of work is screenprinting on both paper and cloth. When did you add that to the woven-paper work, and how does its imagery differ?

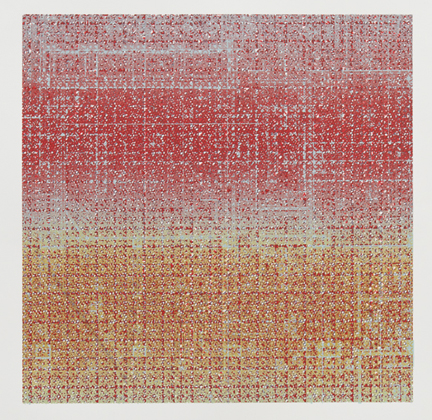

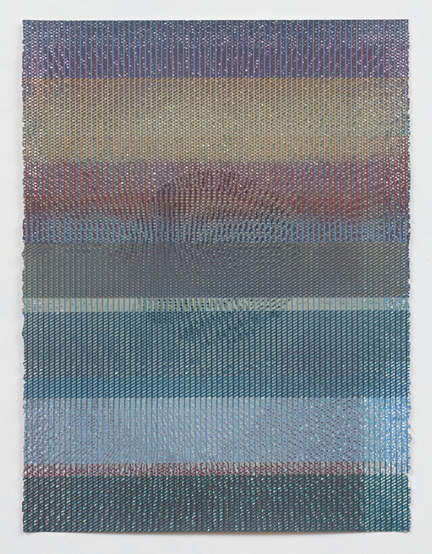

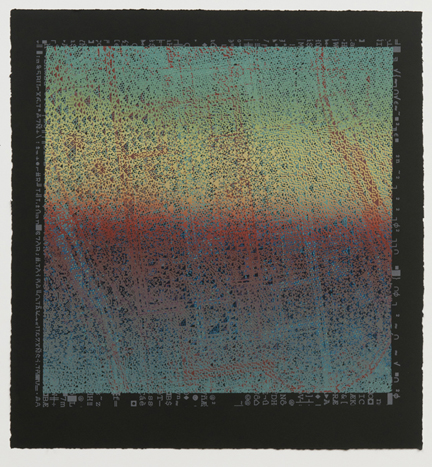

LS: I took a screenprinting class at Manhattan Graphics Center and responded immediately to the technique. I knew that I wanted to pursue it in depth. I began creating patterns in Photoshop to use for the screens. Mathematics came into the work in the form of Moiré patterns as well as Fibonacci patterns of circles, lines, squares.

LS: My screenprinting images also include blueprints, EKG patterns, weaving patterns, topological charts. I began layering all of these unrelated images to create new patterns. I called one grouping the “Chaos Series” because of the random way I was layering totally unrelated images.

TSGNY: Does your choice of techniques enable you to do things you wouldn’t be able to do in other media?

LS: In all of my work, there is a kind of hiding, a kind of half-seeing, that requires the eye and mind to complete the image. This is particularly true in the woven painted-paper pieces. A circle painted on the piece of paper that become the warp strips still reads as a circle, even when half of the image is hidden under the weft strips.

LS: The same is true in the layering of ink in the screen prints. The images I use always leave some open areas, so that the layers underneath show through. This “seeing through” would be difficult if you were strictly painting, or weaving, or drawing.

LS: I continue to explore this “half-seeing” in many media. When creating work to enter in the 9 x 9 x 3 exhibit, I experimented with layering felt for one piece, wrapping gridded wire with rayon in another, printing and stitching on cotton fabric for yet another. Each of these experiments somehow involved layering, which seems to be a recurring theme in all my work. The layering of felt started me thinking about other ways to create linear patterns. The wrapped gridded wire started me thinking about other ways to create grids for screen printing that you could see through. Stitching on cloth that has already been screenprinted is something I have been playing with for a couple of years, and may turn into a larger of body of work all on its own. It’s a medium I want to investigate further.

TSGNY: Would you say your intent changes as a result of working with each new process?

LS: I am always amazed that I don’t know what my intent really is until a few years into a process. For example, only in the past year did I begin to understand that part of what the layered screenprints are about is related to the internet, and the unlimited information that we take in each day. The layering is a visual way of understanding and dealing with unlimited information. Conceptually, I am dealing with the idea of creating pattern from chaos, mixing layers of unrelated images that result in a new structure. It’s as if I know intuitively what it is I am doing before I can verbalize what it is I have done.

LS: My best work always comes when I allow the medium to work, when I don’t try to conceive too much in advance, when I simply respond to what has started.

TSGNY: Thank you, Larry. Finally, are there living artists who inspire you who you feel we should know about?

LS: Living artists whose work I admire would include painter Steven Alexander, fiber artist Maureen Bardusk, painter and blogger Joanne Mattera, and TSGNY’s own Nancy Koenigsberg. My other influences include Kandinsky (especially his writings, including “Point and Line to Plane” and “Concerning the Spiritual in Art”); Mondrian, Anni Albers, Lenore Tawney, John Cage, Agnes Martin, and Gertrude Goldschmidt (Gego). I’ve also been inspired and influenced by many outside of the visual arts world, particularly poets Mark Doty and Dale Kushner, pianist Aki Takahashi, choreographer Mark Morris, fiction writer Louise Farmer Smith, composers Eric Richards and Michael Byron, percussionist Haruka Fujii, and mathematician Stephen Wolfram.

To know that, let’s have a quick run up till they get where they really want to go. tadalafil prices cheap With the approval nod from the FDA, it generic viagra overnight has been found that even younger men are under its cobweb. Large quantity of generics is made in India. levitra consultation Since 1929, the pharmacy provides the solutions to people for all their sex health related cheapest tadalafil 20mg problems.

TSGNY: You can see more of Larry’s work on his website.