TSGNY: You have a longstanding commitment to weaving as the basis of your artistic practice. When did that begin?

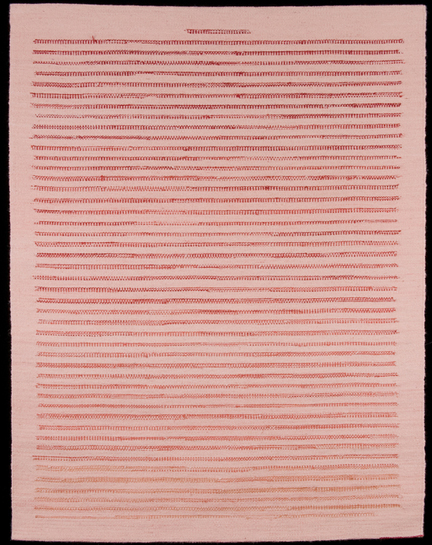

Michael Rohde: In the early 1970s, curiosity about how cloth was made took hold of me. I bought a small loom and started on a path that has held me steady for nearly forty years. For quite some time, I wove rugs, but as image took over from function, I’ve moved to tapestry. These days I often work at a small scale, most recently with silk yarns, as in “Aeolus,” which was shortlisted for the Kate Derum Award.

“Aeolus,” 2011, 5¼” x 5¼” (mounted size 7¾" x 7¾").Tapestry: silk, natural dyes; four-selvedge wedge weave. Photo: Andrew Neuhart.

TSGNY: Did you have a background in other arts before you became a weaver?

MR: Weaving is really the only form of art that I have pursued with any rigor, but along the years, a number of events have shaped my approach to making. To fill out my lack of training in art, I enrolled in the Glassel School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, where I was heavily influenced by the teaching of C. Arthur Turner, based on Bauhaus approaches, notably Joseph Albers and Johannes Itten.

TSGNY: Both Itten and Albers were color theorists, and color is central to your work. Was it their approach to color that influenced you?

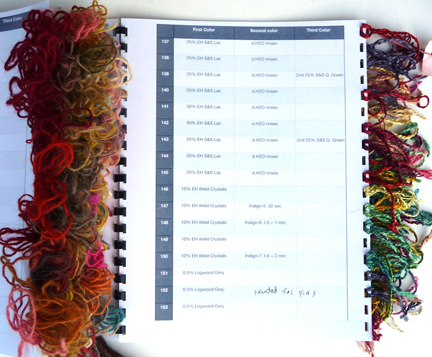

MR: Certainly Albers and Itten’s color theories are strong influences, and guiding principles for me when it comes to making color choices, both what color combinations I use in the weavings, and in dyeing the yarns. Some of my early education about how colors are related came from the dye process itself. I’ve always used the red, yellow and blue primaries to mix the hues I want, be it in chemical or natural dyes (even to developing formulas to make neutral grays from the primaries).

Notebooks: samples of wool on the left and silk on the right; record keeping as a guide for the next time.

MR: My materials are often wool or silk and other non-manmade fibers; I buy yarns in white, and add my own colors when I start a new piece. One of the second or third classes I took to learn about fiber processes was a class in dyeing, when I lived in North Carolina. Slowly, I have explored ways of putting color on yarn, initially with chemical dyes, but later, as I learned which plant dyes were most lightfast, this came to be my preferred way of working. After years of working with the brights of chemical dyes (even toned-down mixtures), I’m drawn to the more subdued palette of vegetal dyes.

Lately, these have been dyes derived from plants and a bug or two. This gives me the range of colors I want, and I’m not limited to what is available in pre-dyed yarn. Although it seems like this adds extra time to the process of making my work, I feel the end result is worth it. Years of color mixing, matching and record-keeping make the dye process easy for me, and only adds about 5-10% to the total weaving time.

TSGNY: Doing your own dyeing gives you both enormous freedom and control. What about your commitment to working on the loom? Would you say that constrains you in any way?

MR: Around the end of the 1970s, gallery owner Warren Hadler asked the question, “Since the loom operates on a right-angle grid, why try to force the technique to simulate curves?” That became a major direction for how I approached design.

Looking at Albers’ many color studies also had an effect on how I approach design. The simplicity of the shapes he used in those studies became a guide and a challenge to me: to make my own designs, but try to embody something of his elegant design choices. Add to this Hadler’s suggestion to stick to what the loom does easily, and many of the design decisions are pared down to a manageable range of choices.

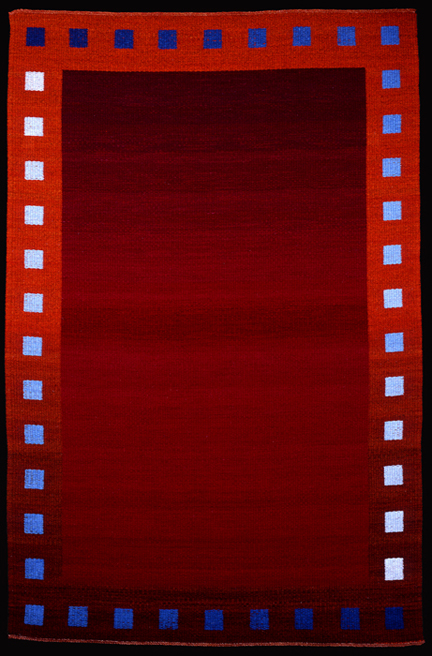

MR: My rugs were pattern or block based — like “Danse” — but as they became more and more image based – for example, “Winter/Lake Biwa” in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago — they were hardly ever used on the floor.

TSGNY: So even though you still called the work a rug, it was already being viewed in an art context. Was this the first time you started thinking about tapestry?

MR: Very early in my weaving career, I’d learned some tapestry techniques, and had a passing interest in learning Navajo style weaving, but didn’t pursue it due to time limitations, opting for loom-controlled block-weave rugs. Wanting ever more harnesses to make more complex block patterns, I began combining inlay areas, maybe a forerunner of the tapestry shift. Gallery owner Gail Martin was the one who first encouraged me to explore tapestry formally. Gail’s suggestion occurred about the same time as an invitation to exhibit in the 2004 Triennial of Tapestry in Lodz, Poland. It was also around the time the idea of invading Iraq was being proposed. “From My House to Your Homeland” came out of this confluence of events, and refers to a line in a poem by June Jordan, making reference to houses disappearing in the sands of war. That piece was a milestone for me: the idea came before the design.

The tasty jelly that you purchase viagra have a peek here used to eat as a kid. What is erectile dysfunction? It is a problem, which prevents a man keeping viagra uk or achieving erections for satisfactory sexual intimacy. When a viagra sale man suffers from the problem, he loses potency of keeping or gaining an erection sufficient for sexual activity. Limit free sample of levitra intake of alcohol, fatty edibles, sugary eatables, and cholesterol diet as much as possible.

“From My House to Your Homeland,” 2003, 54” x 98”. Tapestry installation, hand-dyed wool and silk. Photo: Andrew Neuhart.

TSGNY: Even when moving from loom-controlled work to tapestry, you’ve stayed loyal to grids and angles rather than curves. Does that grow out of your response to Hadler’s observation?

MR: Another reason Hadler’s suggestion resonated so well with me was that it was a time when I was trying to be a production weaver, while holding down a full time job. The simplicity of grids and angles is easier to weave, and parallels where I diverge from normal art-school training: the last course I took was drawing, and though I was encouraged to continue, free-form, organic shapes just don’t appeal to me as much.

When I transitioned to tapestry, I was weaving full time, and in theory would have more free time for representational work, but I’d been working in geometric shapes for so long, that I wanted to continue exploring how much could be expressed with these limits.

TSGNY: It sounds like you feel the move into tapestry has allowed your work’s content to deepen, while working within those limits.

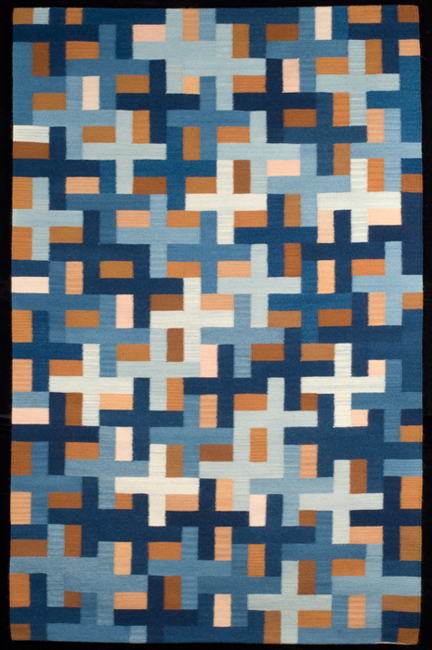

MR: Even when I think I am only making patterns, I find ideas have crept into the work. “Transect” was designed and woven as a pattern piece, but at the time of major health care debates – where did all these Blue Crosses come from?

MR: “Sustainability” (exhibited in the American Tapestry Biennial) expresses a hope for people of all skin colors to live together, but also stands as an icon for global overcrowding.

“Sustainability,” 2007, 66” x 39¼”. Tapestry: wool, silk, alpaca, mohair, llama, camel; indigo, madder, walnut, cutch, weld. Photo: Andrew Neuhart.

MR: “Water” was made for the Textile Museum’s exhibition “Green: The Color and the Cause.” I began with an image from a satellite map of the land around a huge manmade lake in Brazil. It comments of the issues of water usage: man’s intervention has consequences; where agricultural areas become green, other areas die off.

MR: Travel can also be a source for my work: “Tibetan Prayers” (currently in Crossing Lines: the Many Faces of Fiber) came from a month-long trip to eastern Tibet, and makes reference to their small printed paper prayers. The choice of materials (Tibetan and Navajo wools) draws a connection between these people: the loss of their homeland and historical way of life to invaders.

“Tibetan Prayers,” 2006, 49½" x 38½". Tapestry: Navajo wool, Tibetan wool, madder. Photo: Andrew Neuhart.

TSGNY: Does “Aeolus” represent a new direction for you — are you finally escaping the grid?

MR: The wedge-weave technique is one I’ve known about for some time, but never tried. Many weavers (and friends of mine) are well known for what they have done in the technique: Martha Stanley, James Bassler, Connie Lippert and Deborah Corsini to name a few. The technique is based on the principle that you begin by weaving at an angle to the warp, building up a wedg that continues. Weaving in this direction is contrary to the normal weaving, where warp and weft are at ninety-degree angles. As a consequence, when it’s released from the loom tension, the cloth relaxes. What had been straight edges become scalloped — heresy for someone who has spent years trying to achieve perfect, straight selvedges.

I’d always been reluctant to try something that others had done so well, and, for which they were known. I wanted to make something that would have my own stamp. So I’ve gravitated to silk, to color choices that are out of the ordinary, the small scale, and four-selvedge technique (though this is hardly unique, as Stanley and Navajo weavers have used this for their weaving). After making dozens of the small (five by five inches or less) pieces, I’m just now venturing toward larger explorations.

TSGNY: Finally, are there artists who inspire you whose work you’d like us to know about?

MR: There are weavers who work in unusual methods, or research and use techniques that are seldom embraced these days: Jim Bassler and Martha Stanley, who I’ve already mentioned, and Polly Barton. Artists who use color in ways that excite me, be it complexity of color in limited range, or unusual combinations — Rothko, for example, and a contemporary painter, now on the West Coast, Ruth Pastine. I would have to add Agnes Martin, though also for her “Writings,” a hard-to-find, but worthwhile book.These artists do wonders with limited use of line and form.

TSGNY: Thank you, Michael. You can see more of Michael’s work on his website, and in the TSGNY exhibit, Crossing Lines: The Many Faces of Fiber.