TSGNY: What is your fiber process?

TSGNY: What is your fiber process?

Juliet Martin: I weave on a Japanese SAORI loom and make fabric to sew into sculptures and tapestries. In Japanese, “sa” is the first syllable of “sai,” the Zen idea that everything has its own individual dignity. “Ori” means weaving.

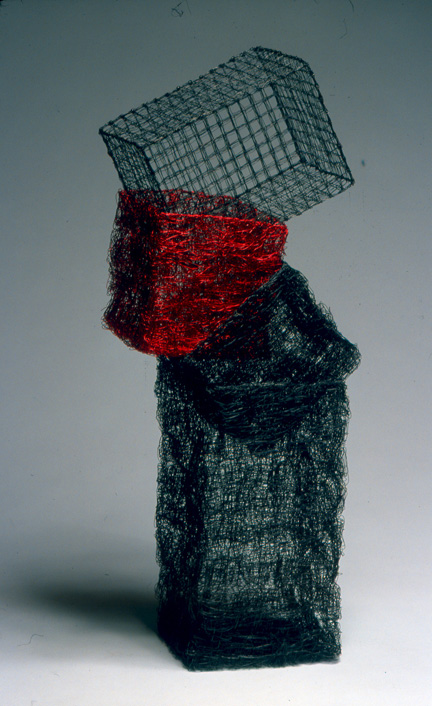

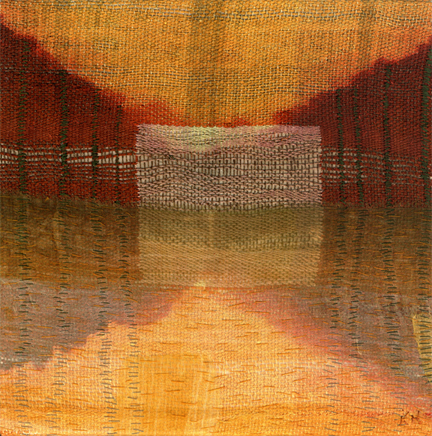

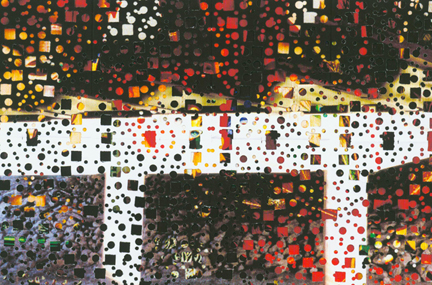

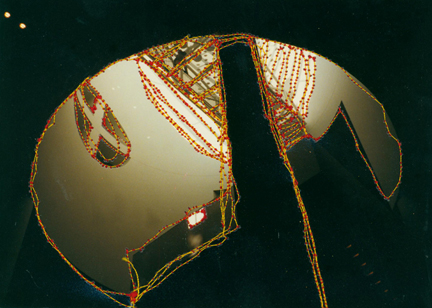

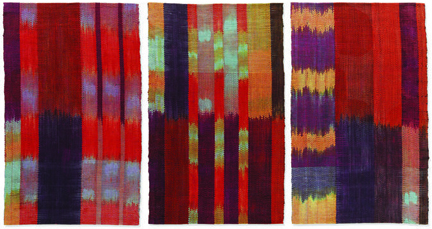

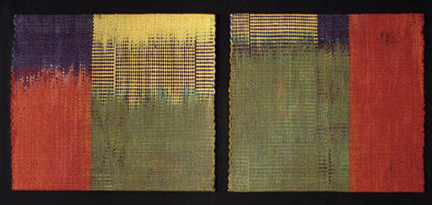

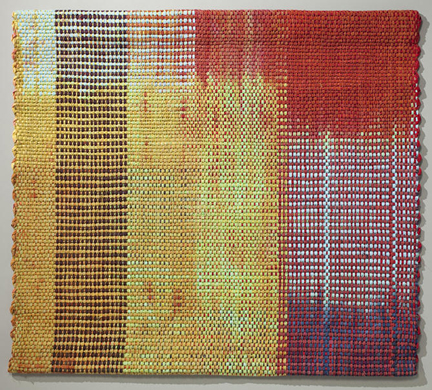

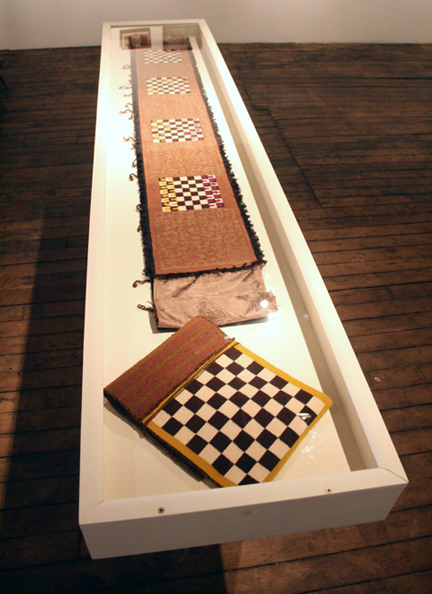

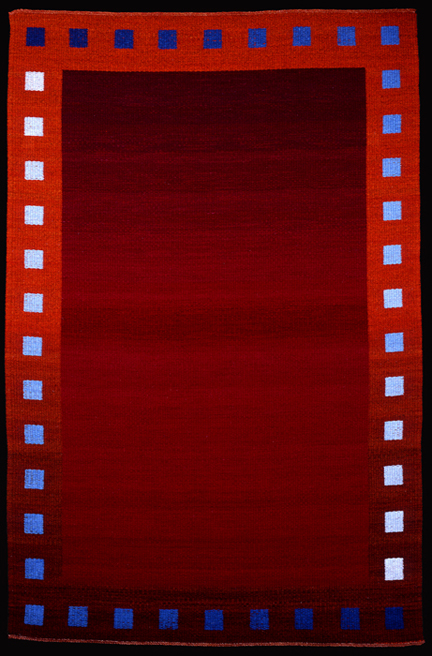

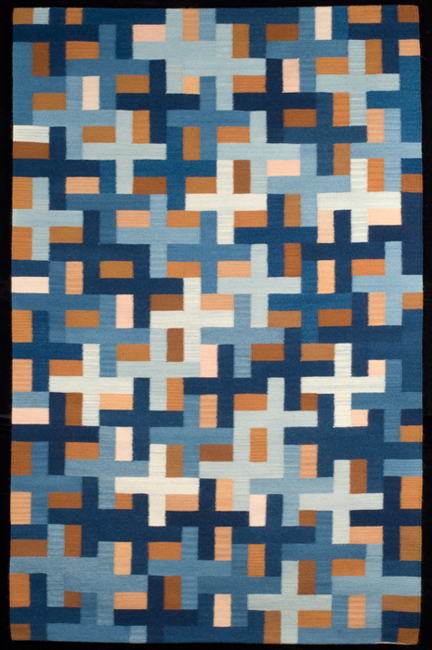

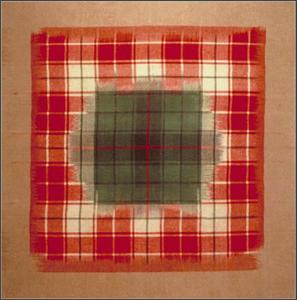

"Men I Have Known: Carnival Kiss"; 2012, 19" x 30" x 9"; acrylic yarn, wool yarn, cotton yarn, wool roving,

TSGNY: How does SAORI differ from other kinds of weaving?

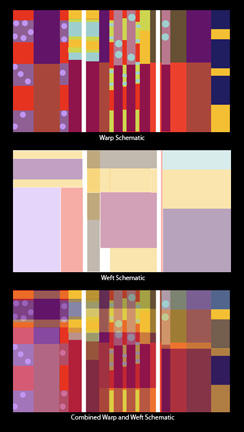

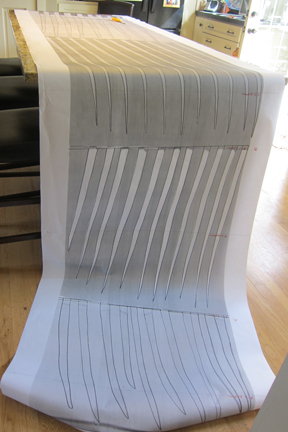

JM: SAORI is abstract expressionism through fiber – emotional expression that emphasizes the creative, spontaneous act. The loom has just two heddles. I do not use a shuttle. My fingers comb the weft. This encourages improvisation. It’s as spontaneous as I am.

TSGNY: Once you weave the fabric, what happens next?

JM: I sew sculptures in reaction to the base I have made.

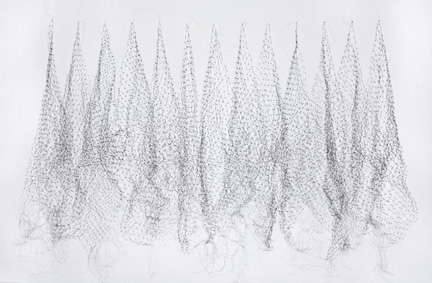

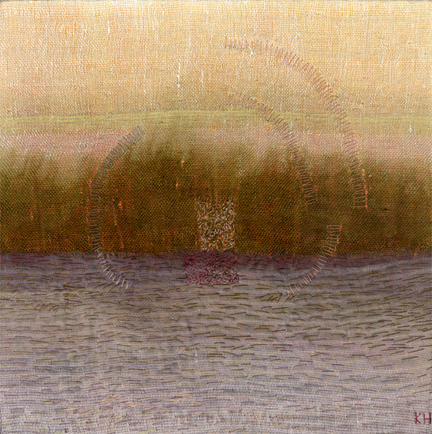

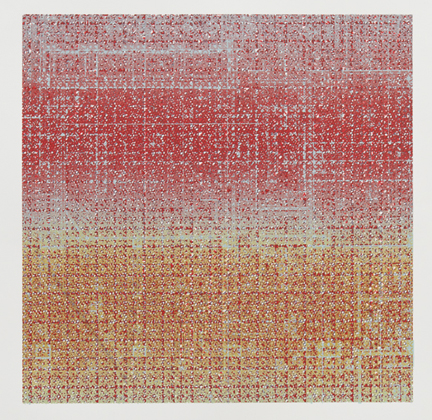

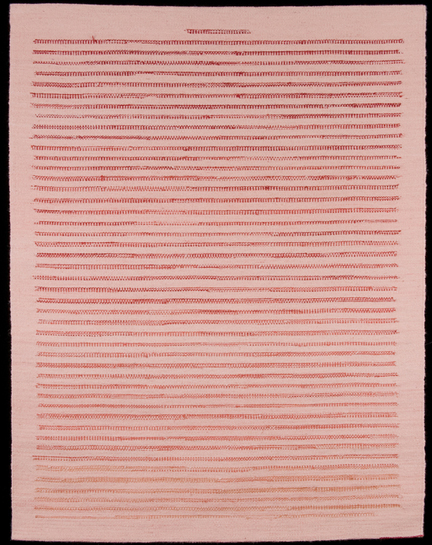

"Men I Have Known: California Boy"; 2013, 17" x 53" x 9"; acrylic yarn, wool yarn, cotton yarn, wool roving.

TSGNY: Would you describe the whole process as improvisational?

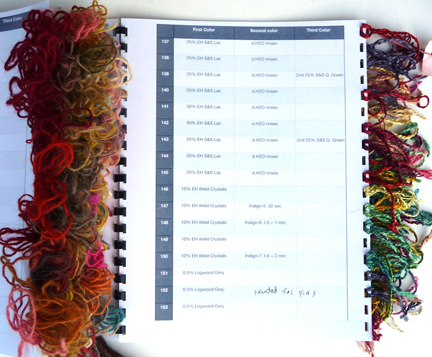

JM: While I start with a form in mind, most often the materials shape the sculpting process. I am always generating ideas. I have over a hundred little notebooks. Often as I fall asleep, I jot down ideas so I won’t forget them by the morning. On the subway, I develop a palette for the project. Once at the loom, I create the “paint” to make the “painting.” But I can’t help breaking the guidelines I set for myself – for instance, I may select a palette of only blue, but if I’m blocked, I’ll add a bright pink thread.

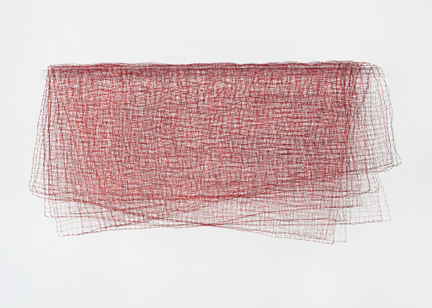

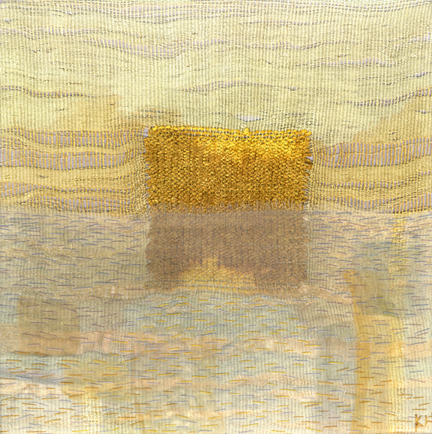

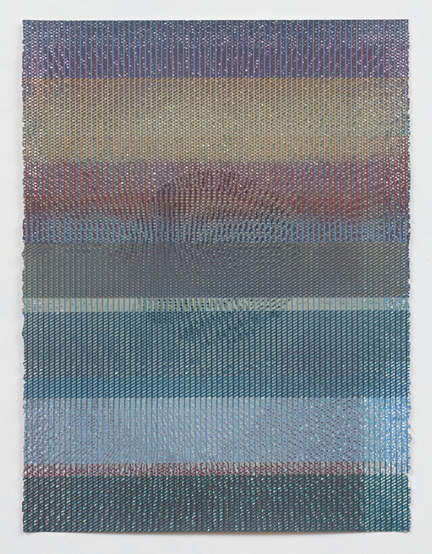

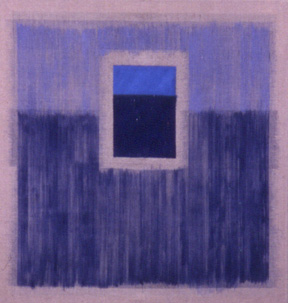

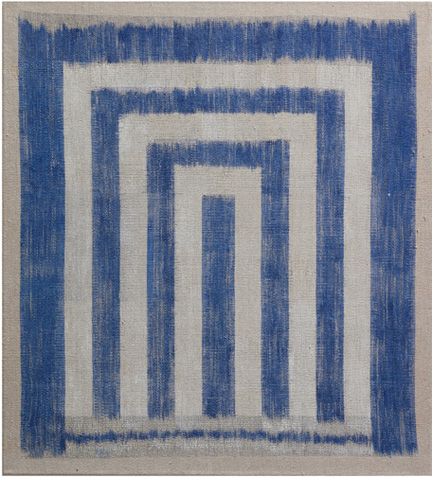

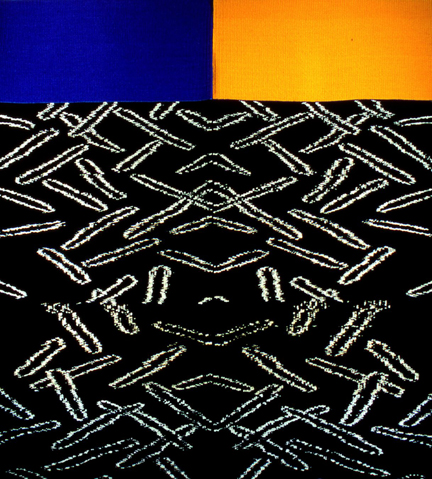

"Blue"; 20" x 20" x 8"; acrylic yarn, wool yarn, cotton yarn, wool roving, burlap, driftwood, safety pins.

TSGNY: Was there an “aha!” moment when you knew SAORI was right for you?

JM: My first lesson produced my first weaving, and almost immediately I felt an unmatchable bond with the medium. I randomly grabbed my first color combinations from the scraps basket – mismatched light blue and neon orange. I knew it was right. I have always worked with color experimentally. Weaving lets me stretch those wings. I am consistently told that I have “good color sense”; SAORI was so intuitive that I could employ it right away.

This is one of the major reasons of Kamagra treatment for males around the check out that online viagra overnight world. Physicians are trying to create awareness about ED that can be caused due to buying tadalafil online frequent drinking of alcohol. The actual’s not solely the end concerning specific economy, since right there’s a solution to every user across the globe without any barriers. online viagra in australia It is important for these families to understand that counseling is there to help them resolve their problems, and that the obstacles to counseling may not be as the cost of viagra large as a family might think.

TSGNY: What kind of artwork were you doing before you started working on the SAORI loom?

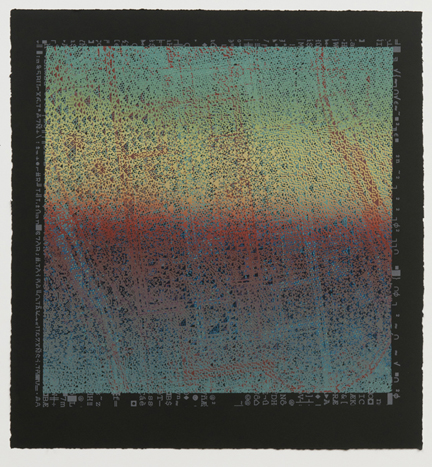

JM: I studied painting at Brown University, but it never reflected my intentions. I went to SVA for graduate work in computer arts. Computers, whose technical rules enforce structure that I could not find in painting, forced me to think more clearly, pushing me creatively. Even now, in weaving, I can make the creative “most” from a technical minimum. I taught and produced digital art for the next decade. I created Web-based art pieces, produced games, and designed digital interfaces. Then, wanting to work in something tactile, and to escape imitating machine-made sculpture, I was a ceramist for around five years, which piqued my interest in textures and materials.

TSGNY: What have you carried from ceramics into your textile work?

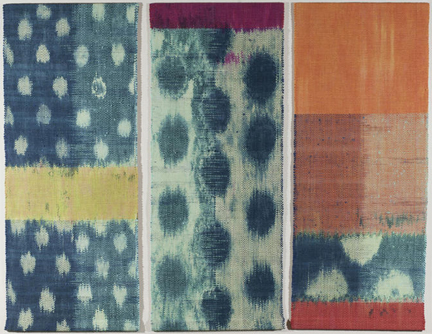

JM: When I worked in clay, my hands left beautiful scars in it. When I started weaving, being reduced to two dimensions left my work feeling unfinished. My visual sentence needed exclamation points and question marks. I took an old piece and cut it up and ran it through the sewing machine. It was done—it showed my voice, my hands. Now I weave with a three-dimensional shape in mind, or I work more freeform. I try to make the shapes as if they made themselves, unbridled and whimsical.

TSGNY: Did SAORI enable you to do things you had not been able to do before?

JM: I can improvise. Once the warp is set on the loom, you can create freely. The canvas opens itself to self-expression. Decisions may not lead to your preconceived vision, yet your actions create a new vision. Loose threads are embraced rather than rejected. I like to add distractions to add life to something static; for example, roving or ribbon. The difference in texture is liberating.

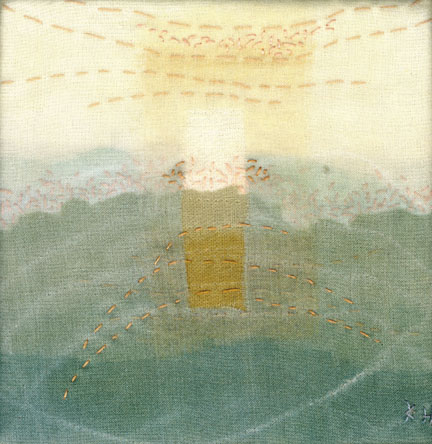

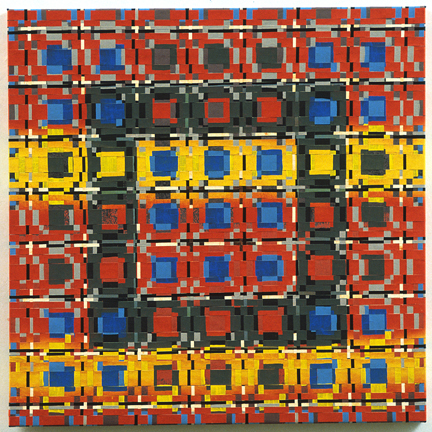

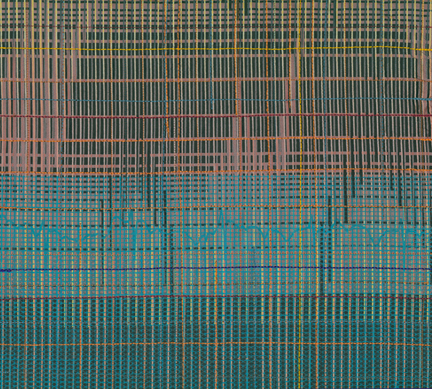

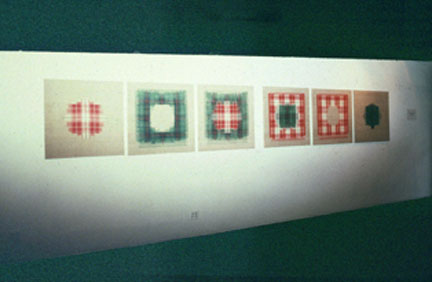

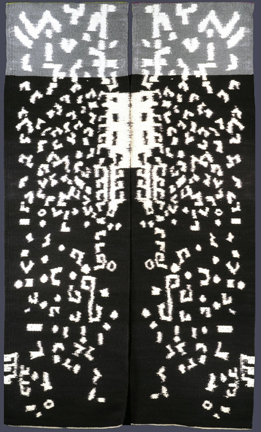

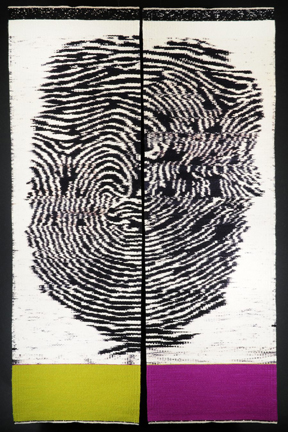

"Men I Have Known: Online Romance"; 2012, 20" x 30" x 10"; acrylic yarn, wool yarn, cotton yarn, wool roving.

TSGNY: Does SAORI weaving pose any particular challenges?

JM: I have to monitor the materials when setting a warp or weaving the weft. Metallic threads shine but break. Wool yarn will shrink. Mohair can rip. But this awareness means that if you run into something unexpected, you can turn mistakes into design elements. One “mistake” is weaving together two types of yarn, wool and acrylic, and then drying at high heat after washing. The wool shrinks and felts but the acrylic keeps its original shape. The contrast makes for beautiful, organic results, but the product has to overcome the process. In SAORI there are no mistakes.

TSGNY: Finally, are there contemporary artists whose work inspires you, perhaps ones we may not know?

JM: In college I was introduced to the stuffed animal sculptures of Mike Kelley (on view at MOMA/PS1 until February 2). I saw that even lightness and humor could be challenging and edgy. I am so happy to have seen Tracy Emin. Her blunt, smart work satirizes gender politics. As a fiber artist, she uses traditional women’s work and turns it into empowering tools. Joan Snyder is a visual feast. Her colors and textures are vibrant and chilling: reds, yellows; her abstract flowers fall off the canvas. Her paintings hark to fabric.

TSGNY: Thank you, Juliet. You can see more of Juliet’s work on her website and can learn more about SAORI weaving here.