TSGNY: Would you describe your work as fiber art?

TSGNY: Would you describe your work as fiber art?

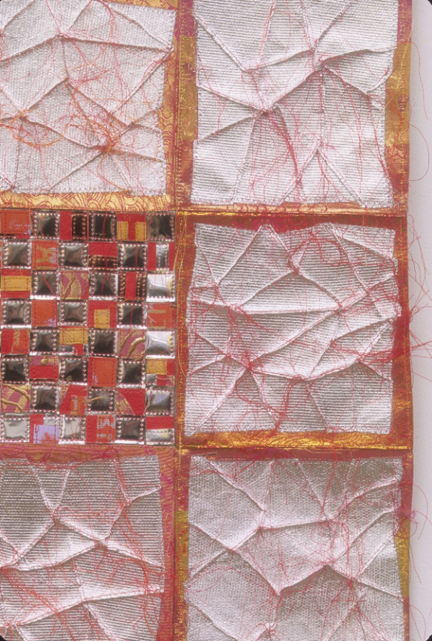

Kathy Weaver: I use both traditional fiber techniques and ones not normally associated with fabric. I delight in the quilt and appliqué techniques used by my grandmother and mother. But essentially, technique is a means to convey ideas and I want the viewer to look beyond the technique to the content.

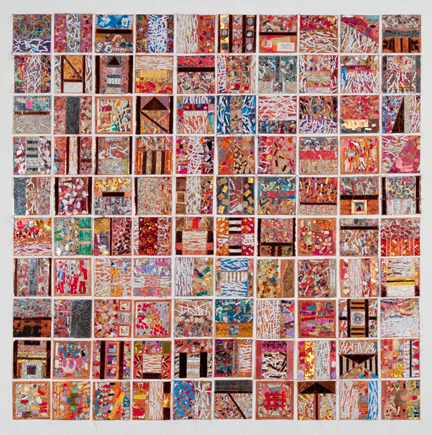

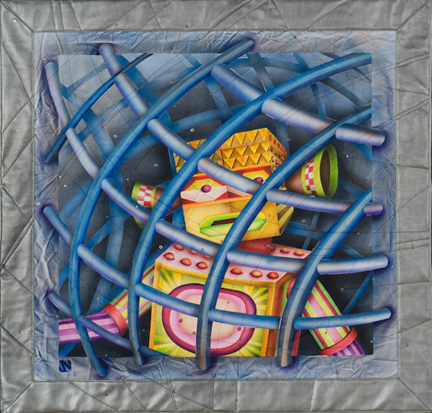

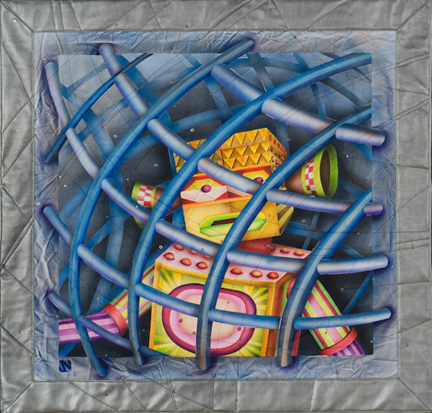

"Robo Sapien Agent 5,"2006, 44” x 44”, Airbrushed, machine quilted, embellished.

KW: Since my subject matter is often robots and ideas generated from the field of artificial intelligence, I deliberately chose airbrushing in order to render in a mechanistic way, without evidence of the artist’s hand.

Preparations for airbrushing.

TGSNY: What kind of work did you do before you started airbrushing?

KW: I was a painter, and still am. I use gouache and egg tempera. I sometimes paint vignettes on canvas and attach them to my textile work. Sometimes I draw and paint directly onto the fiber. Airbrushing seemed like a natural evolution. As an art teacher in the public schools I loved exploring materials and trying new media with my students, so taking up another instrument, the airbrush, as a means to paint, was not intimidating to me. It seemed perfect for the robots’ “skin.” So I enrolled in an airbrush class at a local college where I learned how to airbrush on motorcycle helmets, gas tanks, fish and bird decoys, and taxidermy forms.

Airbrushing

KW: I’ve always loved the advertising designs and coloring of the era I grew up in. Many of these ads were airbrushed rather than photographed. I also like the look of medical illustrations as well as cutaways and schemas for products and product parts. When I was young we had the run of an electronics factory with which my dad was associated and I loved seeing the engineer’s drawings and how-tos, as well as the renderings of the final products, usually transformers or TV components.

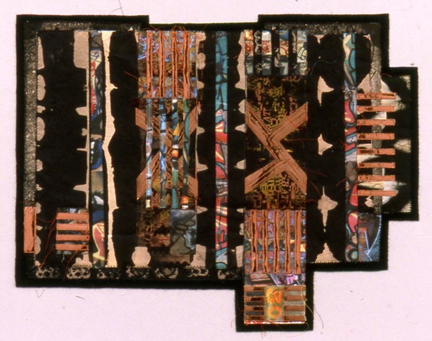

“Cyborg Female 5: Stripped of Instinct,” 2004, 90” x 54”, Satins, silks, velvets, airbrushed, hand embroidered, hand quilted.

TSGNY: When you’re in your airbrushing gear, you certainly look as much scientist as artist. Can you walk us through the steps of your process?

KW: I compose the work in one of two ways. I may create a small color drawing which I enlarge by means of a projector onto a large piece of paper. Or I work intuitively directly on the bridal satin, the substrate for the textile paints. I use white bridal satin for my work…and sometimes black. In the first method, I use the full-scale drawing as a cartoon, tracing each section or division of color onto freezer paper. Then I tape all these pieces together like a giant puzzle and iron it onto the fabric. I methodically remove the hundreds of taped pieces and proceed to airbrush each section one at a time, lifting off to airbrush and re-ironing, lifting off, re-ironing, until the piece is finished. With this method the work is always covered by paper so that I must imagine the colors as I airbrush. After the last tiny piece is airbrushed, I peel the paper away to reveal the finished work.

Airbrushing with stencils

KW: With the second method I use masks and stencils and can see the work as it progresses; the image develops as I paint. Although airbrushing looks very spontaneous, it is a laborious process requiring great patience. There is little leeway for mistakes; the process is akin to the layering, additive process of watercolor painting.

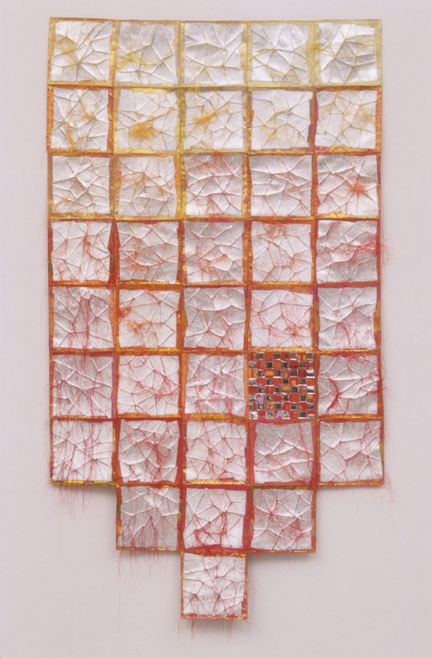

“Mimetic Concerns,” 2010, 44” x 57”, satin, airbrushed, hand quilted.

TSGNY: Are there other challenges to the airbrushing process?

KW: Yes, mainly involving proper ventilation. When I built my studio I installed a ventilating system and I stand under the hood of the vent to paint. My environment is this: I wear a respirator, protective clothing, gloves, and shoe coverings, while standing under a noisy ventilating hood. The airbrush’s hose is plugged into a compressor, which, although called “Silent-aire,” hardly is. With all my gear on, I look pretty robotic myself. All this tends to separate me from my surroundings, which in turn places me in a different mental space. In order to communicate with anyone I must remove all my gear and step away from the area. In this bubble I feel very free to create. It’s just me, my decisions, and my “canvas”; time passes in a different way.

“Strategic Alliance,” 2008, 48” x 55.5”, Satin, airbrushed, hand quilted.

TSGNY: How does the range of materials you incorporate enhance the body of your work?

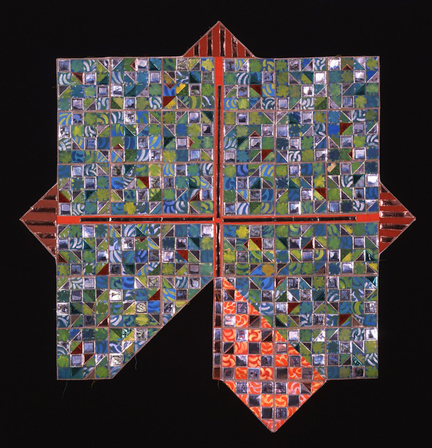

KW: I love working with a variety of materials. Some of my favorite Chicago Imagist artists, H. C. Westermann and Karl Wirsum, showed their stuff and told their stories using a wide variety of materials. What my fabric pieces, drawings, paintings and sculptures have in common is the theme of robotics, nano robots or artificial intelligence.

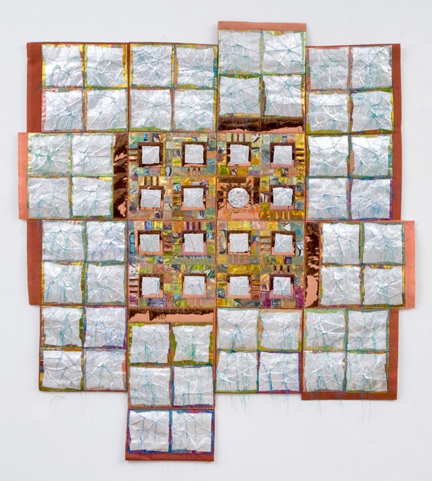

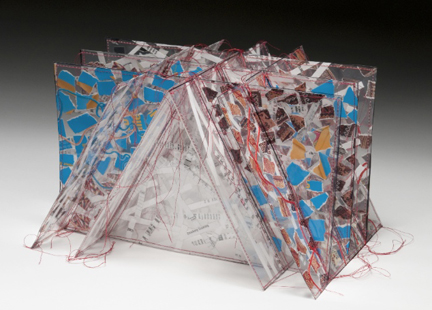

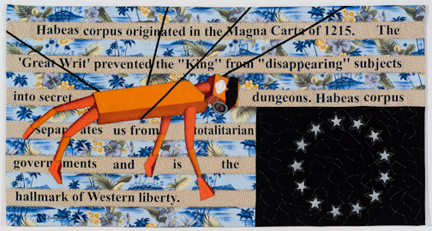

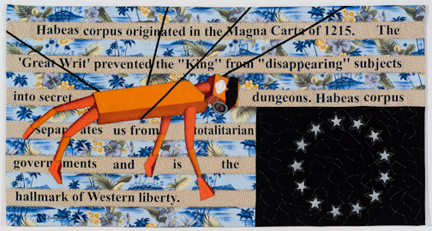

“Habeas Corpus: The Great Writ,” 2008, 35” x 68”, Cottons, nylon line, airbrushed, hand-stitched.

KW: The various materials overlap and enhance one another. For example, the charcoal drawings I am doing at the Rehabilitation Institute are translatable to thread line via embroidery, yet the finished drawings stand alone and have been exhibited in that form. The toys that I deconstruct and transform into robots are kinetic sculptures, yet use fabric and texture to express themselves. The larger papier-mâché sculptures have sensory devices, recordings, embroidery, and airbrushing.

“LMR VII (Mother),” 2009, 59” h x 24” w x 16”d, Fiber, papier mâché, found objects, horsehair, metal, sound and light, airbrushed, embroidered.

KW: The sculpture LMR VII (Mother) is airbrushed on fabric, with embroidery. The appendages and head are papier-mâchéd and airbrushed. The head has sensors so that when a viewer approaches a recording is activated. Also, a door in the back of the head opens and a light is activated, revealing a scene in the inside of the head.

“LMR XII (Captain Le Rocher),” 2011, 12” h x 12” w x 3”d, Bronze, airbrushed, embroidered, painted.

KW: Recently I have been making some bronze sculptures in a stage-like setting. In the sculpture LMR XII (Captain Le Rocher) I cast the bronze figure using the lost-wax process. The background of the box is airbrushed satin, which is also embroidered and quilted. The outside of the box is airbrushed and also painted with egg tempera. The sculptures reiterate the 2D robot quilts but have the added feature of the solidity of the bronze contrasted with the fragility of embroidery, the machine-made futuristic look of my bronze robots contrasting with the labor-intensive stitchery that reminds us of another era.

TSGNY: Would you say there’s an ongoing tension between the presence of the “hand” in the textile processes you employ and the deliberate absence of the hand you’re going for with the airbrush?

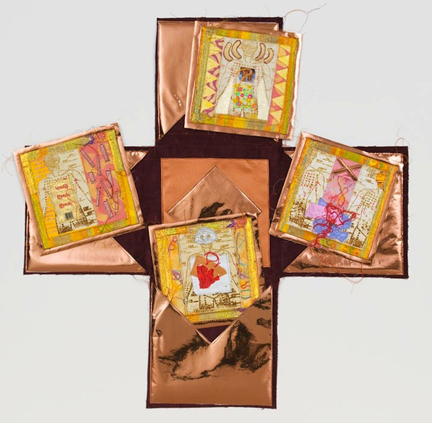

KW: In all the work there is an incongruity in the use of soft material for hard objects and sharp thoughts. The embroideries show a duality between the softness and familiarity of satins and threads and the complexity of forms from organic chemistry, cellular biology and engineered robots. The labor-intensive hand embroidery has a feeling of slow Penelopian rhythms, reminding us of a distant pre-technoid era.

“Fire Slinger,” 2010, 48” x 46”, Satin, airbrushed, hand embroidered, hand stitched.

KW: There is also an eerie incongruency in the fact that humans often relate very personally to technological devices, particularly those in which they have a relationship born out of necessity. I am currently drawing patients and devices at The Robotic Lab at The Rehabilitation Institute in Chicago, a hospital and research facility for traumatic injury victims.

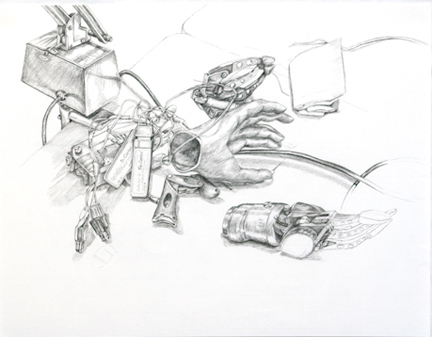

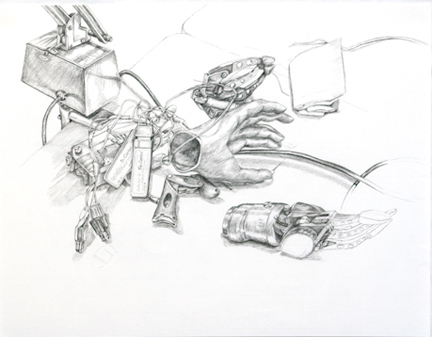

Much of my work has been about the military-industrial complex and the amount of money, not to mention human waste, that goes into the management of war. I was appalled at the number and kinds of injuries being sustained by civilians and vets during the Iraqi and Afghan wars, so I decided to do some research, which led me to The Rehabilitation Institute in Chicago. This research facility and hospital is doing amazing work in advanced prosthetic devices. The majority of their patients are not war victims, as those patients would most likely be treated at VA hospitals. The people I am observing and drawing at this facility are victims of traumatic injury. (If they are victims of war I don’t have access to this information.) I am currently drawing in the hand lab, which is receiving funding for research from the government for the advanced development of prosthetics.

TSGNY: How do you view this particular form of human-robot interaction, compared to your earlier depiction of robotics?

KW: I have the utmost respect for the roboticists and bio-engineers and doctors there who are working so hard trying to make life a bit more palatable for traumatic-injury victims. Mostly, in my drawing sessions of patients who are testing devices, I am humbled by the incredible energy and mindset it takes for them to adapt to their disabilities. The patients are awesome in their perserverance to get some mobility back. As for the traumatic brain injuries, I do not have access to these patients. It would be too disorienting and interruptive of their concentration for me to be in the room drawing while they are working on devices. Words cannot express how sad it is to see young adults being totally cared for by their parents.

“Biomechatronics Development Lab 2,” 2010, 27.5” x 33.5”, charcoal pencil on paper.

KW: As for how I view this form of human-robot interaction — I would have to say with mixed feelings. I am inspired by the technological advances and the people making that happen, and appalled that we need this effort. Both come out in my work, by trying to do beautiful drawings (which will become embroideries/mixed media on fiber) of the patients and devices I am observing, and, concurrently, by doing a series of airbrushed quilts of “disaster” robots about the ravages of war on people and the environment inspired by Brecht’s “Mother Courage and Her Children.”

It’s the juxtaposition, the contrast of where we’ve been and where we are going, that I highlight by using both a needle and thread and the airbrush. As in science, in my art and in life, things are never what they first appear to be. Upon closer inspection, more is always revealed.

TSGNY: Finally, are there artists who inspire you whose work you’d like us to know about?

KW: Most of my inspirations come from the ideas of other artists rather than their medium or techniques. I love the work of William Kentridge and Sue Coe. After seeing a recent show of Lia Cook’s work at Duane Reed in St. Louis and talking with her about the differentiation between her dolls and humans, I felt an affinity or parallel to the border crossings between my robots and the human condition I am expressing. This is the “uncanny valley” that I am continuously exploring — so oftentimes, what scientists write interests me much as what I see.

TSGNY: Thank you, Kathy. You can find more of Kathy’s work at her gallery and on her website, where you will also find her extensive current exhibition schedule.

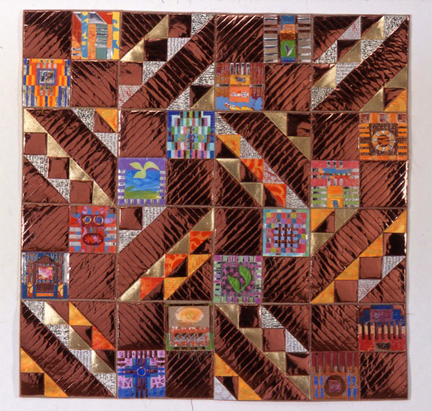

“Simian Interface,”2003, 42” x 59”, Satins, cottons, egg tempera.

TSGNY: Have you always been a fiber artist?

TSGNY: Have you always been a fiber artist?