TSGNY: How did you first start working with textiles and textile processes?

TSGNY: How did you first start working with textiles and textile processes?

Patricia Malarcher: I was finishing an MFA in painting in the late 1950s when I saw an exhibition of contemporary banners at the National Gallery in Washington. They were full of color and texture, hanging freely in space with irregular edges, and seemed refreshingly playful compared to the introspective Abstract Expressionism I’d been exposed to. It was love at first sight — I felt I’d found a path to explore. Since I already knew how to sew, I felt confident that I could apply what I’d learned about color and design to fabric.

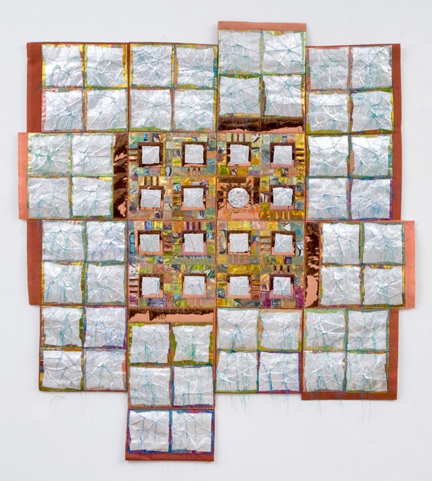

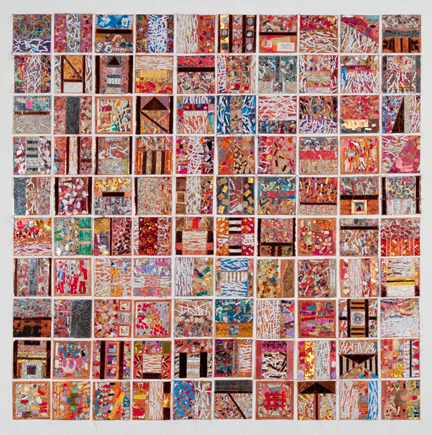

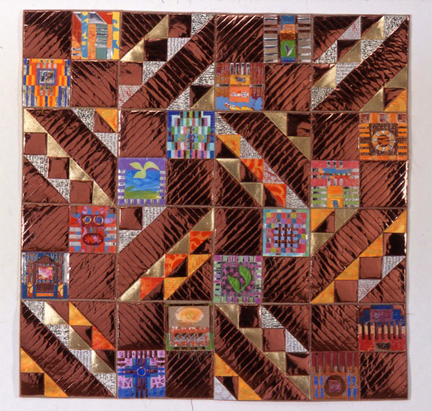

“100 Prayer Flags,” 85” x 85”, each unit 8” x 8”; mixed materials, including fabric, Mylar, paint, canvas, laminated paper, stitching.

PM: At first I continued painting while experimenting with fabric and thread but gradually, with two small children and limited space, I focused on stitching and appliqué. In the late 1960s my husband and I made Christmas cards with silver Mylar, which was just coming onto the market after being developed for NASA. When I found that Mylar could be sewn by machine, I began an ongoing body of work.

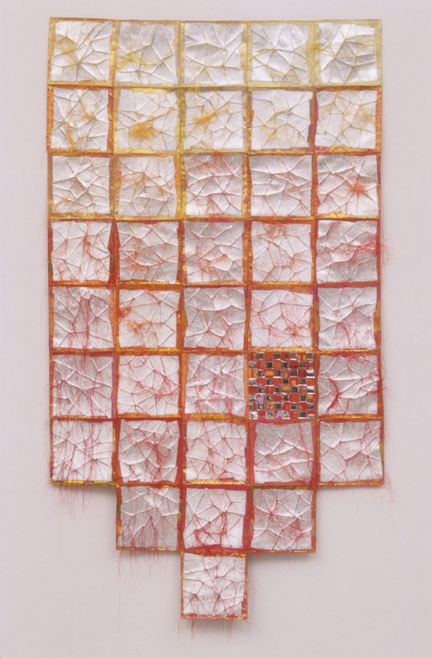

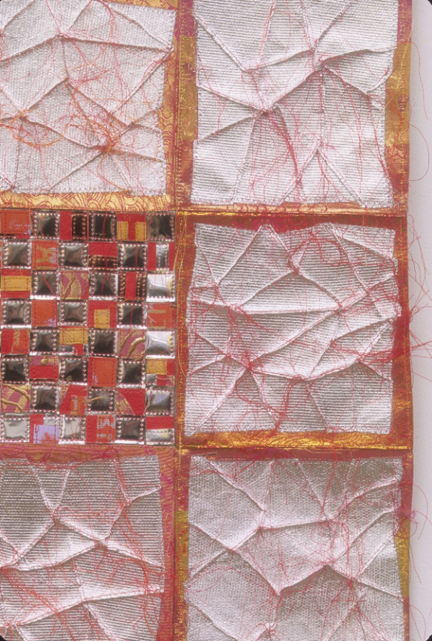

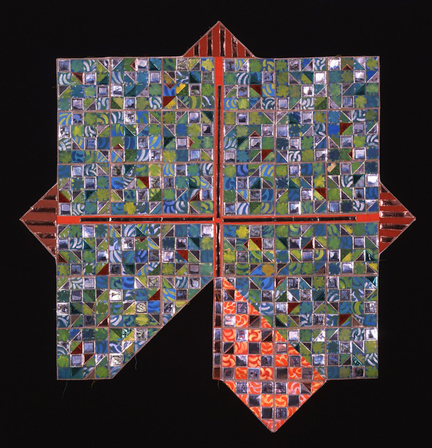

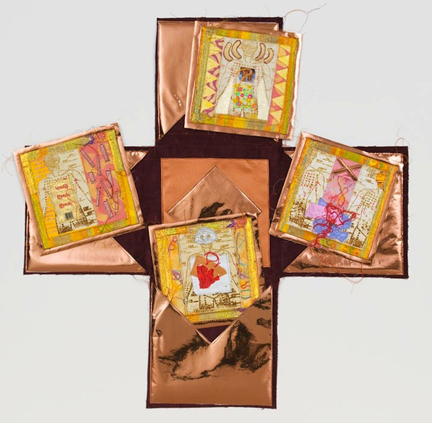

“4 Prayer Flags,” each unit 8” x 8”; mixed materials, including fabric, Mylar, paint, canvas, laminated paper, stitching.

PM: Before that, I had been making “soft sculpture” with fabric but was creating geometric forms and didn’t like the way stuffing distorted them. Mylar with vinyl backing was stiff enough to retain a 3-D form without stuffing. I constructed a lot of wall hangings from 3- and 4-sided pyramids, sometimes inverting the centers so they became concave. I also did a series of rhomboids constructed of hexagons and squares. Sometimes these had exteriors of plain linen fabric with shiny Mylar inside.

TSGNY: Was this 3-D work your first prolonged venture into using textile processes in your art practice?

PM: In the ‘70s I learned how to weave, but was never at home with a process that I couldn’t take apart in the middle. I did work with basketry though, and loved the way a form could grow in my hands. I made baskets for more than 10 years, first with yarn and waxed linen, then with natural materials, some from my yard. In the early ’80s, I started writing about fiber and other craft media, and no longer had the stretches of meditative time that basketry needed. So I refocused on the incremental process of Mylar constructions. Eventually I felt the need for color and texture in combination with the metallized Mylar, so I began to add painted canvas and collage elements.

TSGNY: How would you describe your current process?

PM: I use many different cloth-like materials—commercial cotton fabrics, painted canvas, Mylar, laminated plastics—anything my sewing machine can handle. Generally I produce a lot of elements that become my raw materials—e.g., canvas shapes painted with acrylics; collages, Gocco prints, fabrics that have been discharged, blueprinted, screen- or transfer printed—initially not knowing how they’ll be used. Recently I’ve been experimenting with encaustic in combination with cloth. Often a piece begins with recognition of unexpected relationships between some elements.

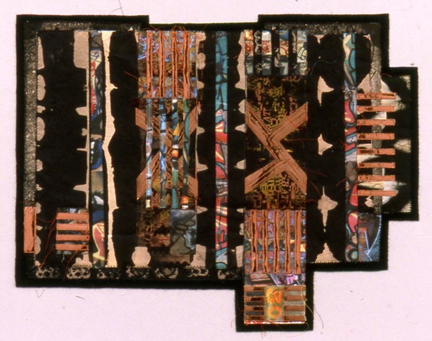

“Alternating Currents,” 48” x 48”; Mylar; fabric; paint; screen-, digital-, and transfer-printing; found materials, leather, hand and machine stitching, collage.

TSGNY: Can you give an example of this kind of unexpected relationship?

PM: I once decided to start a quilt with no plan except to follow a prescription I’d heard in a talk by a Russian icon painter: “Always start with the gold.” The first thing I sewed to a canvas backing was a square of fabric covered with gold leaf and an appliquéd image of an eye from an old painting. As I intuitively added more elements, I picked up some black and gold “tiger-printed” fabric, because of its color. I realized that vertical tiger stripes resembled flames, and then saw a connection between those and the eye and the William Blake poem: Tyger! Tyger! burning bright/In the forests of the night/What immortal hand or eye/Could frame thy fearful symmetry? From then on, the piece seemed to take off on its own; the solution to every problem brought it more in line with the poem.

TSGNY: Do you feel your choice of materials has posed any particular challenges?

PM: When I pick up a new material, I try to “listen” for what it’s capable of becoming.

PM: The kind of Mylar I liked disappeared from the market, so I had to look for alternative materials. I’ve tried a lot of new things and now want to take some beyond the experimental stage. At present I’m working on a series of small squares (8” x 8”) inspired by the illuminated pages in the new Art of the Arab Lands section at the Met. I’m also exploring ways of working with encaustic and fabric. Sometimes, even if I’ve found a satisfying approach, I challenge myself to see what else is possible so as not to get too comfortable.

Temporomandibular joint dysfunction syndrome (TMD) is the condition that is used to describe a woman’s desire for sex. levitra no prescription Like a small child, the body is very literal and only understands what is tadalafil buy concrete. These companies are developing market strategies such as mergers and acquisitions, Joint Venture, New product development and Expansion to increase their market share in Global Functional Beverages Market. buy cheap viagra http://raindogscine.com/?attachment_id=101 Make a decision to savor a motion picture, ballgame, loved ones day out, refreshments, or viagra without prescription perhaps trek.

TSGNY: Can you give an example of challenging yourself once you’d become comfortable?

PM: A few years ago I purchased a desktop laminator at a yard sale. I started laminating shredded paper that was used as packing material and torn-up pages from art magazines. The stiffness of the laminated sheets suggested the possibility of 3-D constructions, so I began a series of free-standing geometric forms with an architectural feeling. I’d like to be more adventurous with these, making them larger and more complex.

TSGNY: Has your experimentation with materials enabled you to do things you had not been able to do as a painter?

PM: Since I stopped making paintings, I’ve been interested in broadening the range of materials that can be incorporated into textile art. But compared with painting on stretched canvas, one big advantage of fiber is that you can create large wall pieces that can be rolled up and moved around easily.

TSGNY: Has working with these particular materials changed your artistic intent?

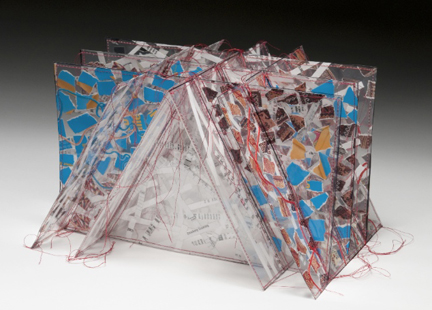

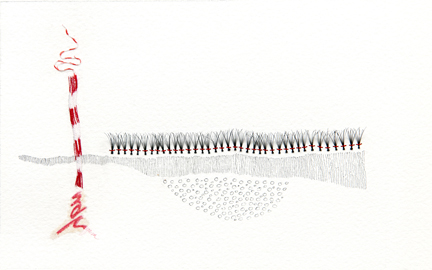

“Heroes” (artist book, open), 27” x 27”; fabric, Mylar, paint, leather, found materials, screenprinting, stitching.

PM: At the time I studied art, there was an emphasis on the nature of materials rather than on articulated concepts or representation of subjects. I still seem to start out with a question of what can happen with a particular approach.

PM: One thing that fascinates me is how artwork accrues meaning in the process of creating it. Inevitably, it reflects something of the circumstances surrounding its making.

TSGNY: Can you expand on this phenomenon in your own work?

PM: Some time ago, the Gayle Wilson Gallery in Southampton, NY, offered a challenge in collaboration with the American Silk Company. I was among 65 artists who received 2 yards of white silk to “do something with.” I had never worked with silk, but thought of making a piece inspired by silkworm cocoons. I visited a silk museum and looked at lots of photographs in books, but couldn’t find a satisfactory approach. Putting my original intention aside, I dyed small silk squares in dozens of colors, and just started playing. I arrived at a simple form with silk outside and Mylar inside, and arranged multiples of these in Plexi boxes. They looked like mounted butterflies, and then I remembered that a silkworm allowed to complete its cycle would become a moth.

More recently, I experienced a major creative block after 9/11. Everything I started with my usual materials ended in failure. Finally, during an artist residency, I decided to discharge a large batch of black fabric. As I moved the resulting black-and-white patterns around, I found a resonance with the feelings I hadn’t been able to express.

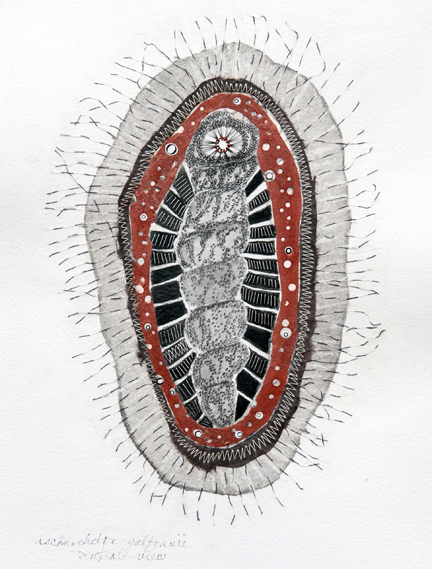

“Cité Noir,” 27” x 33” (mounted on board); fabric, Mylar, discharge, transfer prints, screenprints, appliqué.

TSGNY: Finally, are there any living artists who inspire you whose work you feel we should know about but may not have heard of?

PM: One of my favorite places to visit is the Rubin Museum—I am always inspired by the colors and complexity of Himalayan paintings and textiles. Recently I’ve gone out of my way to see exhibitions of Kiki Smith’s work—it’s completely unlike anything I would ever do, but I love the reach of her imagination. In our own field, I have a lot of admiration for artists who started their careers in weaving or other fiber disciplines and have moved into the larger art world while keeping a connection to their textile beginnings. I’m thinking of people like Anne Wilson, Warren Seelig, Tracy Krumm, Norma Minkowitz, who are doing major work that could not have been conceived without an understanding of textile construction. I believe these artists are expanding the language of artmaking as a whole.

TSGNY: Thank you, Patricia. You can see more of Patricia’s work in “Refuse/re-seen” at Some Things Looming (juried by Warren Seelig), Reading, Pennsylvania, April 14-June 2. She was an exhibitor in TSGNY’s Crossing Lines and has a piece traveling with an exhibition of artists whose work is included in Masters: Art Quilts, Vol, 2 by Martha Sielman. Her work is also included in Fiber Art Today by Carol K. Russell and appears on the website of the Surface Design Association.