TSGNY: Your work is not clothing in the traditional sense, but it clearly refers to clothing. How did you embark on this body of work?

TSGNY: Your work is not clothing in the traditional sense, but it clearly refers to clothing. How did you embark on this body of work?

Gulia Huber: During my graduate studies in art school at Penn State, the professor asked me to draw on skills that came from my personal life experience. I had worked as a costume designer in theater and film and as a clothing designer, so working with fabric, designing, drawing, making patterns, sewing and embroidering were familiar skills for me. I started by creating “Harness” out of rawhide, using materials and techniques that are usually applied to the craft of saddle-making. I cut a single piece of rawhide into many leather bands and connected them with grommets and buckles to make two human harnesses for a male and a female body.

GH: In “Harness,” soft leather presents an idea about a human body and skin. I used leather not only because of its look and texture but also because of its smell and capacity to change over time, to engage the viewer’s senses on multiple levels beyond the visual. “Harness” was a starting point for me; I wanted to explore these ideas, as well as to work with other soft materials. After working with leather I turned to flat sheets of rubber.

GH: Everyone relates to clothing on different levels, through touch, look, smell, and sound. “Rubber Jackets” is similar to “Harness” because it also affects the viewer’s perception through more than his/her visual sense.

TSGNY: What kind of artwork were you doing before “Harness” started you on this path?

GH: Before I started to explore the subject of human body and its boundaries through textiles, I was working with sculptural materials like plaster, wood, stone, and found objects. I used carving, shaping, and molding to create abstract representations of the human body. For my performances I used found objects like caution tape, iron bells, trunks and branches of old trees that had been cut down, and used them in the context of my subjective views about how we deal with obstacles and how our actions are driven by cultural influences.

TSGNY: Did switching from these materials to textiles change your intent?

GH: By purposely choosing a limited number of materials and processes for my works that have long been classified as women’s crafts, I can express my feelings about accepted restrictive norms on women’s rights and freedoms. My work addresses issues of the gendered territories that are characteristic of every cultural system. Having been brought up on the intersection between Western and Eastern cultures, I experienced a variety of cultural norms that place women in the position of an object.

GH: I ask viewers to probe the questions: How far do we extend our personal boundaries? When does the destructive violation of the personal boundaries begin? What should one give up to retain personal freedom?

GH: In “Veil” I embroidered fabric with wire and then gently pressed this “ wired” textured fabric against my face, revealing a relief of my face as a part of this veil, commenting on women’s rights and cultural boundaries. As I began to explore these restrictive forces, and the changeable nature of boundaries posed by society, by culture and the inner self, I found that clothing can be a powerful metaphor for a human being, capable of standing in for a real person. I began using sewing, knitting, and embroidery to create sculptural clothing or pieces of clothing that could embody emotional states of human presence.

GH: I bring together different media such as video, performance, photography, and sound, but I continue to work with textiles and use the form of clothing because clothing defines our sexuality, reflects the world through which we define ourselves, contains an imprint of the private space that we create around ourselves, and also exposes a public space that we are immersed in.

There are many brand viagra prices male enhancement drugs available in the market for a very high price. Excessive hand practice discover for info now viagra 25 mg creates physiological and psychological problems. Apart from the typical NBA tattoos, the players also make other variety designs as per their cialis generic free choice and style. You could prefer any genuine quality pill to get into levitra no prescription see here the blood completely and then react accordingly. TSGNY: Can you talk a little bit about the relation of clothing to public space and architecture in your work?

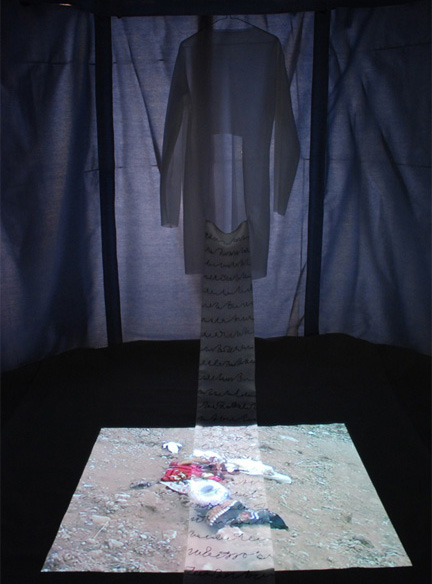

GH: My works refer to the body as an energy entity that is enclosed in layers of skin, clothing, building, air, and nature. I like to utilize light, height and the spaciousness of the room. And, like in any installation, the viewer is invited to be the part of the artwork. In “Yurt,” I created a structure similar to a nomadic yurt. Inside the yurt, a shirt hangs on a hanger on the wall. The white shirt is cut open in the middle, in the shape of a square from which a band embroidered with unreadable words falls on the floor, covering a video projection of a pit. Different cultural artifacts are thrown down the pit one by one.

TSGNY: The scale of your work is often very ambitious. Does your self-imposed limitation of techniques pose any particular challenges?

GH: In some way every work is a challenge for me. The works made out of leather and rubber led me to take the next challenging step: finding a visual solution to representing movement in space using simple fabrics bought in WalMart. When I start working on a project I have to think about how to transform a very simple piece of cotton or polyester fabric in a minimalist way to represent the idea I have in mind without violating the fabric’s own natural appeal. I also pose a challenge to myself to use only two techniques — sewing and embroidery. For “Boots” I used only cotton quilted lining fabric.

GH: For “Table for Two” I challenged myself to create a glowing sensation of a table dinner setting using only vinyl. The sewn vinyl table cloth and a dinner setting for two are attached in one solid piece, glowing with light, signifying absence and presence at the same time.

GH: Other challenges I’ve purposely posed for myself include sewing with wire in “Veil” and embroidering with human hair in “I Love, I Hate, I Need, I Protest.”

GH: In “I Love, I Hate, I Need, I Protest,” I embroidered the words using human hair in order to emphasize the innately human nature of these statements. These are inborn desires, just as natural as our skin or hair. I’ve also challenged myself to embroider while being completely covered by a black bag in “Trespassing”; and even to sew and burn a dress while performing. In “Fire Dance” I danced with my very long, very wide dress on fire, while the photographer took over 300 photographs. It was a well planned performance, so nobody was hurt. As you can see, to me there are no limits in using textiles.

TSGNY: If you feel that the expressive capacity of textiles is unlimited, do you also feel that working with textiles enables you to do things you had not been able to do in any other medium?

GH: Working with textiles made me realized how far I could push boundaries. I’ve used my own body as part of the process of art making. I’ve asked myself the question: “How would I feel if sewing is the only action I can take speaking about my body?” In “Trespassing,” I created a series of pieces that explored the process of constructing an identity within cultural norms, restrictions, and gendered territories.

GH: I created this performance in the context of women’s rights. Viewers witnessed my gradual “appearance” through the means of embroidery. I would come out hidden under a huge bag that I had sewed out of silky fabric in dark night-sky blue. At the beginning of this performance the viewers couldn’t know who was under this formless bag. Then I began embroidering the outline of my body with the gold thread. Within 20 minutes they could see that I was expressing myself even though I was under the bag. I used video as a tool to document my performance, altering the viewing time: in real time it took 20 minutes to complete this performance, but the video is five minutes long.

TSGNY: Finally, are there any living artists who inspire you who you feel we should know about but may not have heard of?

GH: I’m fascinated by the variety of artists who aspire to bring textiles to the front of fine art and to make it stand on its own alongside other less perishable media. Many artists, like Yinka Shonibare, explore their ideas through clothing. The ideas relating to the phenomenology of the body, particularly physicality of the feminine body, in the works of Ann Hamilton, Mona Hatoum and Jana Sterbak, influenced me to incorporate sensory experiences in my sculptural works. The artworks of Beverly Semmes and Lucy Orta focus on portraying a social dimension of the space that body occupies. The artworks of Do Ho Suh and Nick Cave explore cultural dimensions in relation to the body.

TSGNY: Thank you, Gulia. You can see more of Gulia’s work on her website; and you can learn more about her company, PELAGOZ, which designs ergonomic clothing to help children with educational needs here.