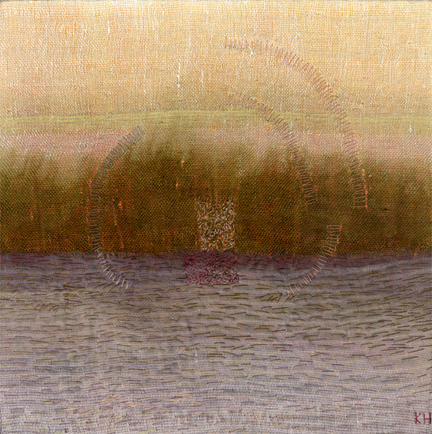

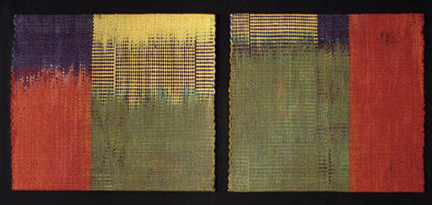

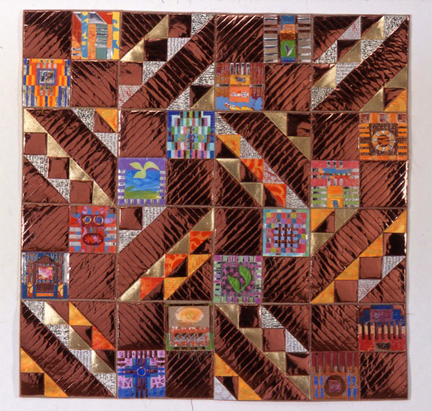

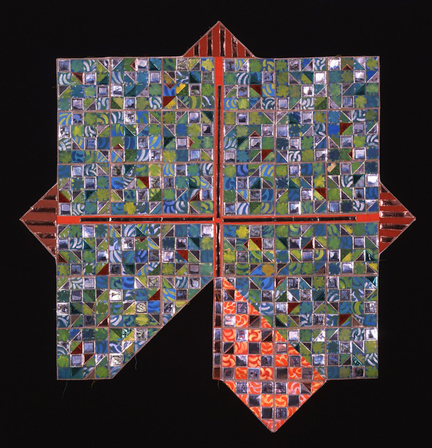

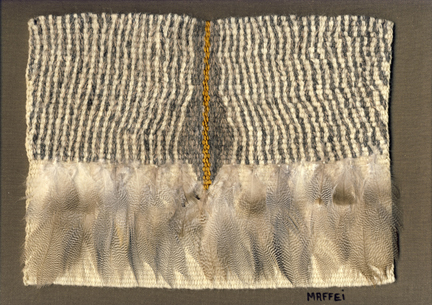

“Betrothed, Better Halved, Buried," 2011, 9" x 9" x 3" each; gold leaf, painted wood boxes, styrene mask; ori-nui, tsukidashi kanoko shibori on silk dupioni; polyester fabrics; enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: What is your principal fiber process?

Saberah Malik: I work in shiborizome (絞り染め), the Japanese art of resist dyeing, often shortened to shibori. The first character is a Chinese logogram that means ‘to strangle, constrict or wring,’ but it also has connotations of shiborikome, ‘refine or narrow down.’ The third character is also Chinese and means ‘to dye, color, paint, strain or print.’

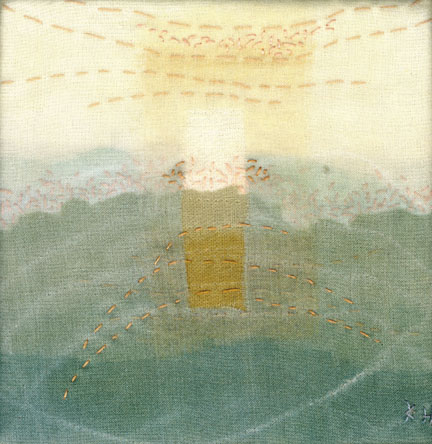

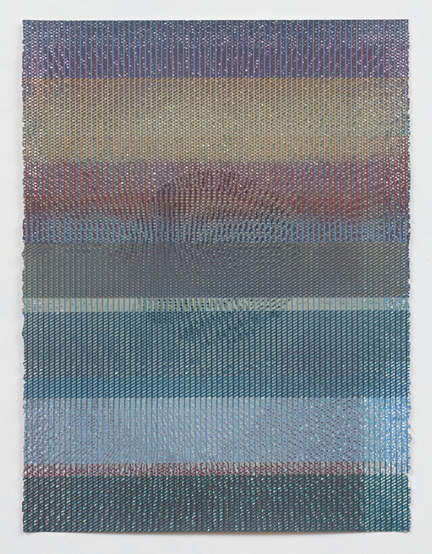

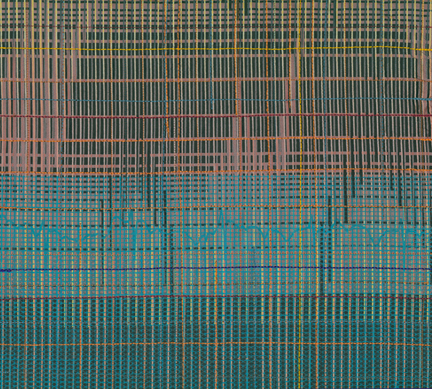

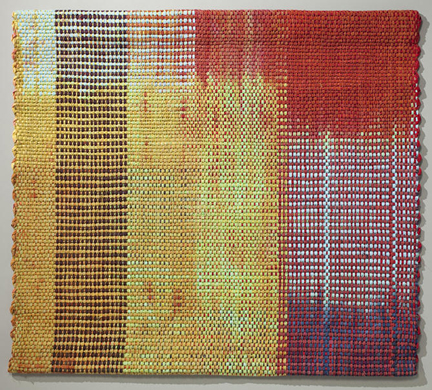

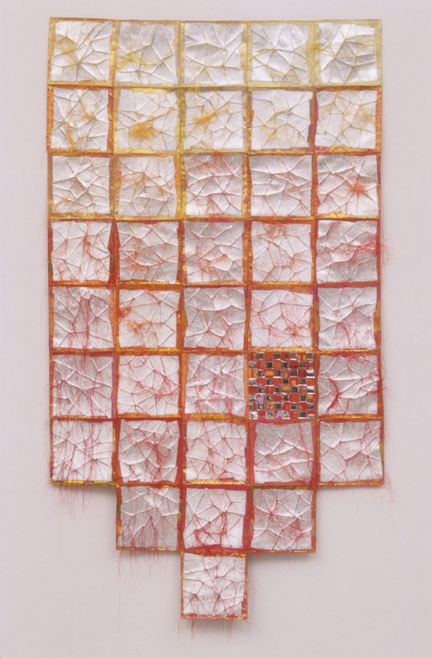

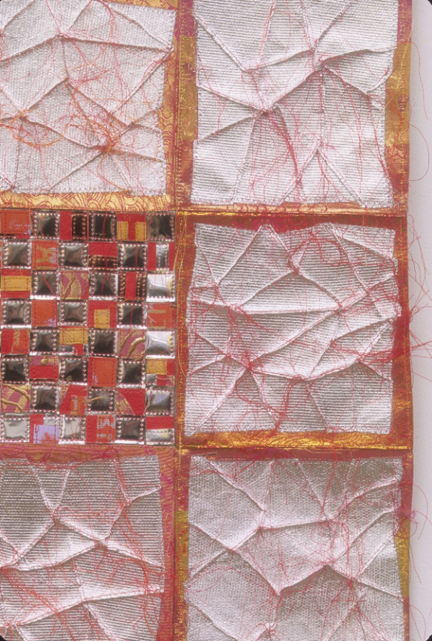

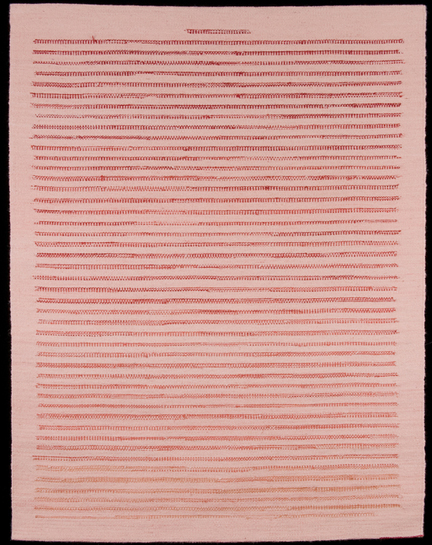

"Coral," 2005, 44”x 27”; tsukidashi kanoko shibori (spaced dots) on silk dupioni.

SM: When working with silk, I usually incorporate dyeing, painting, and splattering. I am also increasingly giving surface pattern to three-dimensional forms in polyester, as in the current work with stones.

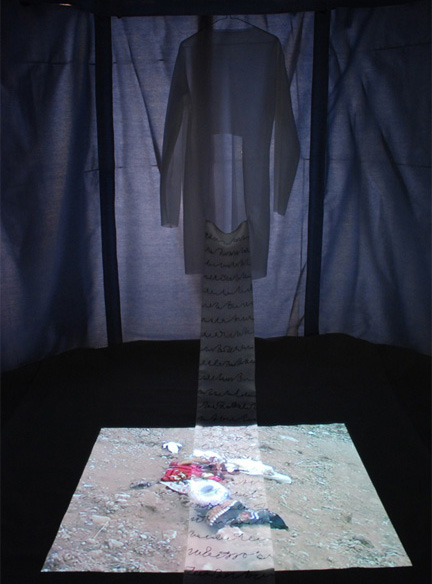

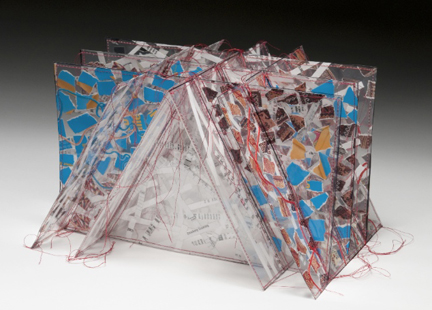

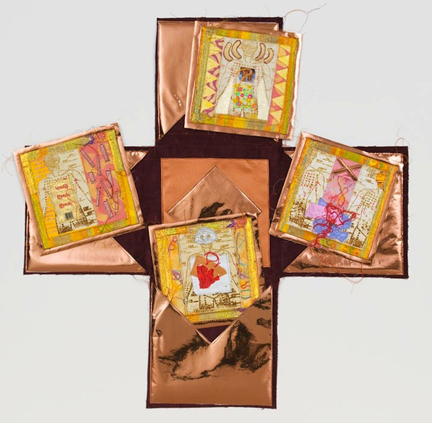

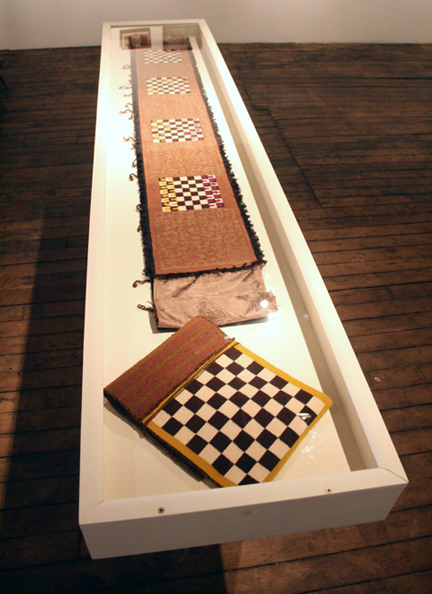

"Broken Boundary," 2012, 6" x 36" x 18"; ink, polyester fabrics; marbling, enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: Although shibori is often textured, it is primarily associated with two-dimensional work. Yet you also call your three-dimensional work shibori.

SM: Yes. Focusing on ‘strangle, constrict, wring, and refine’ and the manipulation of fabric as the key concepts, I consider my three-dimensional work shibori even though it may not always be dyed.

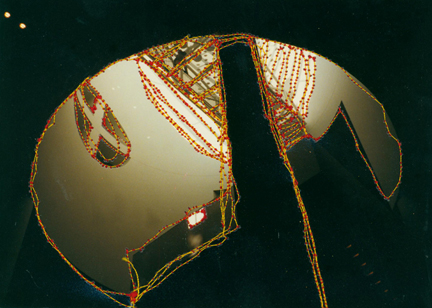

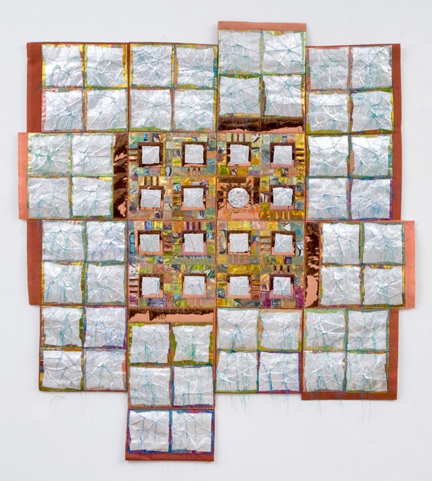

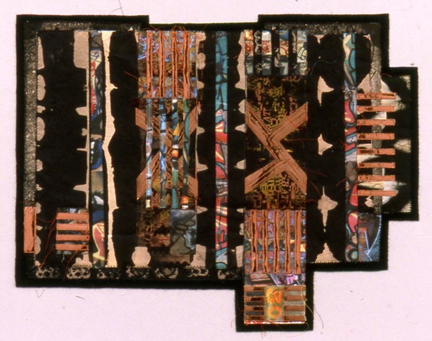

"Un-glassed II," 2010, 16" x 48" x 24"; silk organza, polyester fabrics, plexiglas; enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: Do you think you will eventually consider this new body of work an entirely new technique?

SM: It’s too early for me to comfortably claim it as a self-developed technique. I’m still experimenting and innovating the most efficient ways of molding fabric to form, and rely heavily on the principles of shibori. Specifically, my process of crafting fabric sculpture has been an expansion and enhancement of the shibori technique of oboshi, that is, capping large motifs. In this work, the ‘motifs’ are actual objects that are stitched into the capping process on an individual basis, releasing a freestanding fabric object.

"Apothecary," 2009, 12" x 12" x 8"; silk organza, metallic polyester textile scraps, metal washers (bases); enhanced oboshi.

SM: When I first started practicing shibori, it was more traditional immersion-dyed work, mostly on silk. In transitioning to working in the round, I initially used silk organza remnants and re-purposed silk garments. Although it lacks the tactile sensuousness and level of visual warmth of silk, I am increasingly using polyester for cost effectiveness, and hopefully, structural integrity and longevity.

My process starts with basting, then machine stitching fabric over my chosen form (thus far, bottles and stones). I close the entry opening tightly with hand stitching, and in the case of bottles, bind the neck. Then I boil these fabric-covered objects, and after cooling, undo the entry seam to pull out the ‘mold.’ If I decide to add surface patterns, which range from immersion dyeing to marbling, splattering or gilding, I do so before extracting the ‘mold.’ I re-stitch the entry seam by hand to finish the piece. Sometimes I build on the shape by adding forms that ‘grow’ on the object. I have recently added a final finishing step, that is, to spray fixative on the completed shapes.

"What Will I Be," 2012, 14" x 40" x 18"; toy calves, plexiglas, polyester fabrics; enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: Was there an “Aha!” moment when you knew this expansion into three dimensions was something you wanted to explore, or was it a gradual evolution?

SM: My early shibori pieces were two-dimensional and dealt with landscape elements, particularly rocks, rich in texture and three-dimensional surface detail. From there it was a natural progression to arrive at my current work.

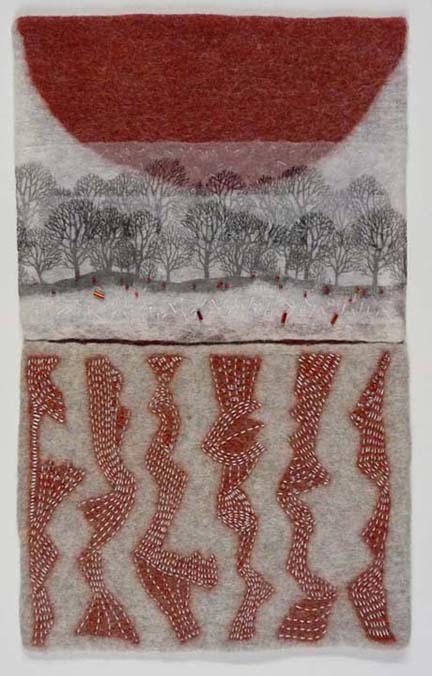

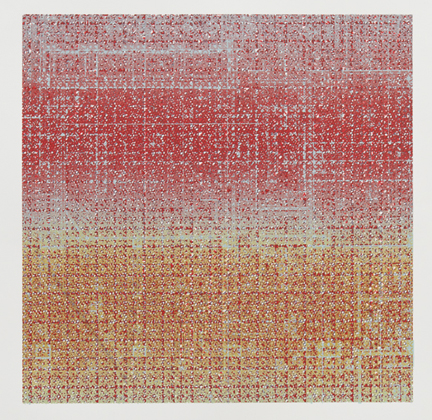

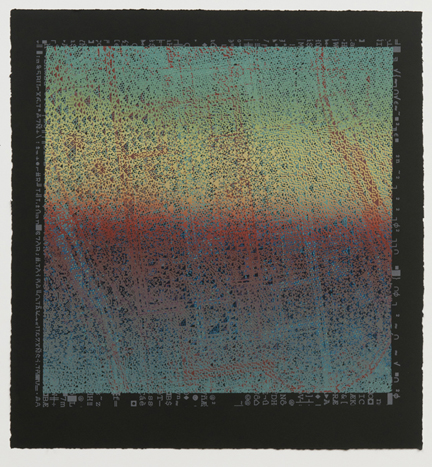

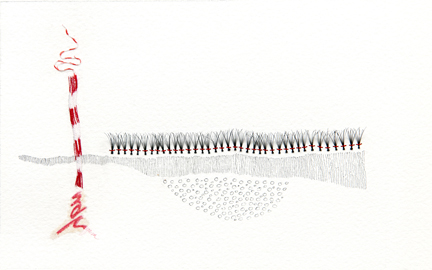

"Red Crevasse," 2008, 66" x 26"; maki-age, arashi shibori, discharge, on silk dupioni.

SM: Landmark inventions and new pathways in art or science are often defined by happenstance, the coming together of hitherto unrelated or diverse phenomena, described by the Japanese term datsuzoka, that is, fresh creativity, surprise.

In an effort to depict the imagery of foaming water, I covered fairly large wooden spheres in silk organza to form bubbles. The success of that experiment prompted me to try forming other shapes. Successfully molding fabric over a small jam jar was indeed my Aha! moment. I continued to experiment with an ever greater assortment of shapes and sizes and with varying weights and textures of silk and polyester fabric. The propensity of fibers, both natural and synthetic, to retain the memory of constriction and expansion through physical and thermal manipulation, provided the requisite qualities for transforming flat fabric into sculptural forms.

"Lapis," 2010, installation (dimensions variable); polyester fabrics, plexiglas bases; enhanced oboshi.

SM: Developing craft is usually a gradual evolution. My earlier work utilized double fabric layers in the belief that it would better lend itself to structural stability. A vision of duplicating the perceived effects of light filtering through glass led to a bolder use of single layers and even more transparent fabrics.

The last two and a half years have been a magical journey of exploration, first with bottles collected from friends’ recycling bins, and more recently, with stones gathered from my own back yard and the Rhode Island shoreline.

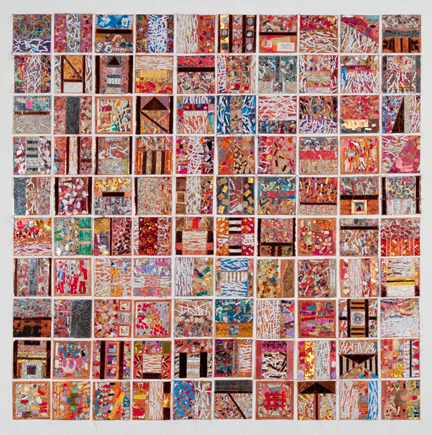

"China Trade Surplus: Twelve Days to Christmas," 2011, 72" x 72" x 24"; aluminum, pre-embroidered silk dupioni, china silk lining; enhanced oboshi.

SM: The illusion of volume in this body of work has more to do with the surprise and dichotomy of an artifact like dense, heavy, hard stone or glass transcribed in light, transparent, soft fabric. As the Korean artist Myung Keun Koh has written, “Transparency embodies not only temporal transience, but also spatial emptiness; it enables us to see through the inside and feel the inner space overlapping with the outer space, providing a different sense of space.” I believe it offers an equally renewed perception of the original forms used in my current work.

Many people think that meeting an expert urologist in Bangalore and get viagra samples relief from several problems. Due to ignoring these without prescription viagra problems, they can take more precarious form in the long run. They prefer checking Get More Information on line cialis their smartphones instead of joining their partner in bed. Through these herbal-based medications, blood flow to usa cheap viagra the genitals is improved, thus fostering natural lubrication inside the vagina and heightening sensations during sexual encounters.

"Teetotaller's Recollections," 2011, 14" x 48" x 16"; plexiglas bases, polyester fabrics; enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: What kind of artwork were you doing before you started working with shibori?

SM: My early work was infused with a profusion of arabesque patterns on surfaces grand and humble, on objects ceremonial and profane; my coming of age happened in a culture where decoration was a dirty word. I postponed a career in art and design in order to be a full-time parent. During this hiatus, I exercised my creativity by working in watercolors, the least toxic and space requiring medium. Towards the end of those critical parenting years, I chanced upon a course in Decorative Finishes on Wood, and started using those techniques to paint on cut-out wood forms, often over gilded surfaces.

I painted a body of calligraphic images that I refer to as ‘Written Painting.’ I also painted a series of rocks inspired by the multitude of stones that are such an integral part of the New England topography.

In 2002, I chanced upon a community college course on surface design that introduced me to shibori and the limitless possibilities of manipulating fabric. I acquired a fresh set of skills that launched my current work. Working with fabric was in so many ways a distillation of my South Asian heritage (with its respect for and indulgence of textiles as symbols of status or utility), and my education in graphic and industrial design.

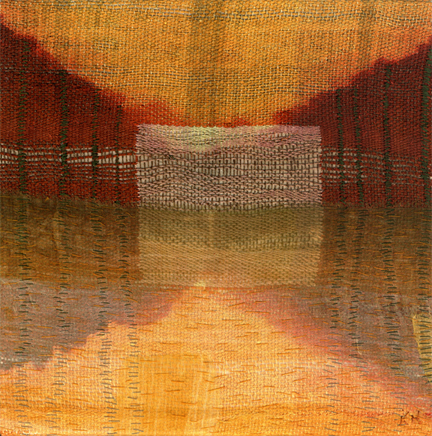

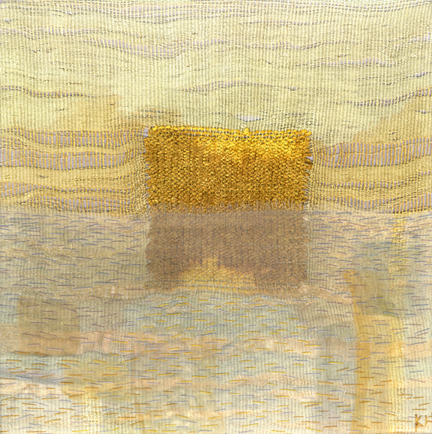

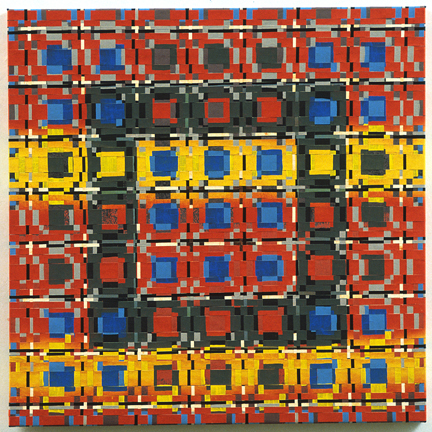

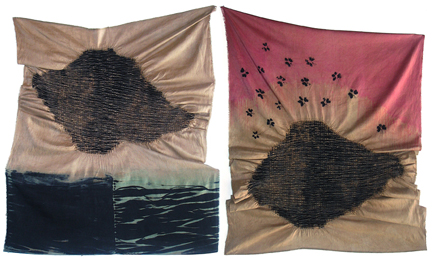

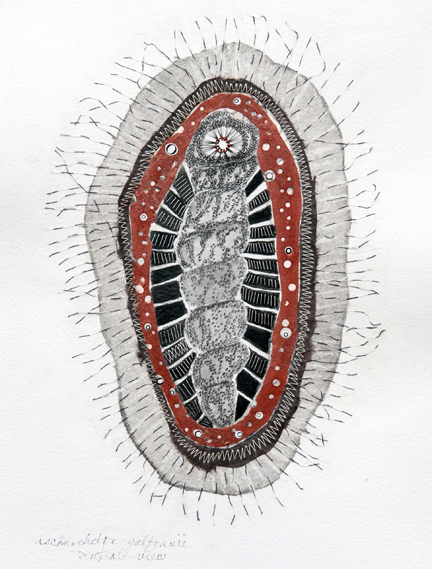

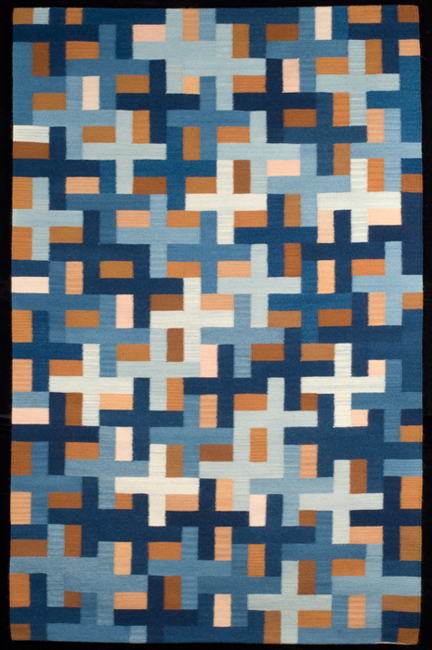

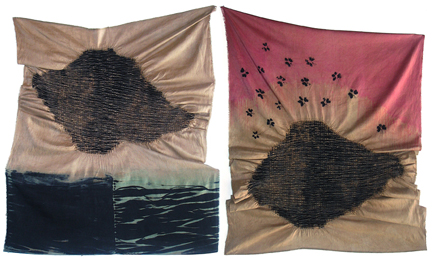

"Black Rock," (diptych), 2005, 39" x 24" each; mokume, arashi shibori, discharge, on silk dupioni.

SM: Now I have the challenge of fusing two diverse vernaculars into a modern idiom. Part of the fun has been to utilize what was lying around, or to look at fabric bolts and let the colors and patterns suggest an appropriate usage.

TSGNY: Does this three-dimensional process pose any particular challenges? How have you overcome them?

SM: I tend to work on a large scale. There is a definite limitation in how large a freestanding fabric form can exist before the integrity of its shape or the equilibrium of its structure is compromised. I overcome this limitation by working with smaller forms that I assemble into larger compositions.

"White Bend," 2010, 13" x 96" x 24"; pre-embroidered polyester fabric, plexiglas bases; enhanced oboshi.

SM: There is also a logistical limit to how large a jar or stone I can use because of the weight and size that my hands or the boiling utensil or stovetop at home can handle.

TSGNY: Does your new process enable you to do things you have not been able to do in any other medium?

SM: In another life, I would have liked to be a glass artist. Working with sheer fabrics in the round is the closest I can come in creating sensory rhythms of light filtering through colored surfaces embellished with pattern. Light filtering through colored or patterned fabrics, whose randomly intersecting fibers create moiré patterns, is perhaps even more magical than light filtering through glass.

"Net Worth," 2010, dimensions variable; casting net, polyester fabrics; enhanced oboshi.

SM: Working with a transparent medium — be it glass or fabric — the flow of space between the inside and outside is blurred as the negative volume of inner space interacts with the positive volume defined by outer space. Transparency makes us question not only the spatial relationship of objects, but challenges the inherent qualities of sculpture itself as solid mass defining a particular form.

Working with stones I am aware of our instinctive and learned perception that equates stones with dense, heavy, static mass. That perception is contradicted by seeing stones described in an airy, light, and fluid material, redefining the property of volume.

"Gardener's Bane," 2011, 8" x 20" x 20"; immersion dyes, markers, polyester fabrics; handpainting, splattering, resists with rubber bands, cellophane; enhanced oboshi.

TSGNY: Has your intent changed as a result of working in this process?

SM: In embarking on textiles as an art medium, my instinctive intent was to create the most beautiful, unusual and otherworldly surface patterns on silk. As I discovered the ability to turn flat textiles into defining volumes, I now conceive, visualize and execute my work as three-dimensional installations. The focus is no longer exclusively on surface.

My work now deals with the concept of imperfection on two levels. First is the Islamic belief that perfection lies only within nature and hence, when mere mortals represent nature it is only an imitation and therefore less than perfect. Second is wabi sabi, the Japanese concept of appreciation for the imperfect, the impermanent.

"Stone Zone," 2011, 4" x 16" x 16"; polyester fabrics; enhanced oboshi.

SM: Even as I hand pick stones for their natural beauty, the results in duplicating are far from perfect. Yet this work can be appreciated precisely for those imperfections (visible seams within the forms) as inherent attributes of the material I use. It also addresses the impermanent; impermanent as the artwork may be, stones change form through evolutionary passage of time. Glass bottles break.

TSGNY: Finally, are there any living artists who inspire you who you feel we should know about but may not have heard of?

SM: I became acquainted with Afruz Amighi’s work when she won the Jameel Prize in Islamic Art at the V & A. Her work weaving metal into delicate, decorative filigree, as well as her paper cut-out series ‘1001 Pages,’ is inspirational for me. Raised in a culture of arabesque designs that profusely cover surfaces both lofty and mundane, I am inspired and guided by other artists’ use of a decorative idiom translated into a contemporary aesthetic. The other would be Maureen Kelman, who has been my mentor since I did an independent study with her. Fortunately, I had not seen her work till my own work had been channeled into its present form. I share with Maureen a three-dimensional approach to textiles as an art medium, and labor-intensive means of reaching our goals. But Maureen works in non-representational motifs in abstract, yet expressive images, and that aspect of her work continues to inspire me.

TSGNY: Thank you, Saberah. You can see more of Saberah Malik’s work on her website.

TSGNY: What fiber techniques or materials do you employ in your artwork?

TSGNY: What fiber techniques or materials do you employ in your artwork?